Pharmaceuticals and sewage treatment

Sewage treatment works are a major defence for the environment against pharmaceuticals which are found in wastewater. Dr Roger Reeve from the University of Sunderland describes recent advances.

Pharmaceuticals in the environment

Concerns over pharmaceuticals in the environment have been growing since the 1990s. Kolpin et al. (2002) reported the presence of large numbers of pharmaceuticals and other organic compounds in environmental waters at sub-mg L-1 concentrations. The effect of pharmaceuticals on aquatic organisms is well-established (Hill et al., 2005), and there is also the possibility of pharmaceuticals entering the food chain. Sex hormones and other steroids attracted early attention because of their endocrine-disrupting properties and ability to bioaccumulate, due to their hydrophobicity. Of current environmental concerns are the majority of pharmaceuticals, which are generally less hydrophobic than steroids. The decline in vulture population in Pakistan has been attributed to bioaccumulated residues of the relatively hydrophilic analgesic diclofenac (Oaks et al., 2004).

Many investigations have confirmed that sewage treatment works are a source of the pharmaceuticals found in streams and rivers (e.g. Heberer, 2002; Roberts and Thomas, 2006; Kasprzyk-Hordern et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2009). Treatment normally reduces the concentration of a pharmaceutical in the water, but a number seem resistant to the treatment, and in some cases an increase in concentration of the drug is found. This review discusses how the properties of pharmaceuticals and their metabolites affect their behaviour in the environment, and particularly during sewage treatment. Examples are taken from papers published in last two or three years. Earlier literature has been reviewed by Jones et al., (2005) and Drewes, (2007). Recent reviews have covered the fate of pharmaceuticals in the environment and in water-treatment systems (Aga, 2008), and the removal of emerging contaminants including pharmaceuticals (Bolong et al., 2009).

Pharmaceuticals entering the sewage-treatment system are largely from human usage. Other discharges into streams and rivers include those from veterinary usage. Veterinary antibiotics in the environment have recently been reviewed in this Bulletin (Bottoms, 2009).

Pharmaceuticals entering the sewage-treatment system are largely from human usage. Other discharges into streams and rivers include those from veterinary usage. Veterinary antibiotics in the environment have recently been reviewed in this Bulletin (Bottoms, 2009).

Environmental concentrations of pharmaceuticals

The environmental concentration of a pharmaceutical is a function of the amount used and other factors such as drug metabolism, and physicochemical properties, which determine the fate of a drug in sewage treatment and in environmental degradation and reconcentration processes. Prescription data are sometimes used to estimate the quantities of drugs consumed, and hence released to the environment (Jones et al., 2002). However, many common drugs are available without a prescription, and concentrations found in environmental waters often show little correlation with prescription data.

Drug metabolism. Only a small proportion of a drug remains unchanged during its passage through the body (Kasprzyk-Hordern et al., 2007; Winkler et al., 2008). Phase I metabolism adds polar groups to the molecular framework. This increases aqueous solubility and allows excretion in urine. Metabolites can sometimes be found in greater concentration in environmental waters than the original drug. The main form of sulphamethoxazole in raw influent water is its metabolite N-acetylsulfamethoxazole (Göbel et al., 2007). Metabolites usually have lower physiological activity than the parent drug, though for paracetamol a minor metabolite is the compound responsible for its toxic effects. Phase II metabolism forms conjugates in which the drug is coupled with a hydrophilic side-group. Paracetamol forms sulphate and glucuronide conjugates (Moffat et al., 2004). Conjugation again increases the water solubility. It is possible for conjugates to break down during sewage treatment to regenerate the original drug and so increase its concentration in the effluent (Roberts and Thomas, 2006).

The environmental concentration of a pharmaceutical is a function of the amount used and other factors such as drug metabolism, and physicochemical properties, which determine the fate of a drug in sewage treatment and in environmental degradation and reconcentration processes. Prescription data are sometimes used to estimate the quantities of drugs consumed, and hence released to the environment (Jones et al., 2002). However, many common drugs are available without a prescription, and concentrations found in environmental waters often show little correlation with prescription data.

Drug metabolism. Only a small proportion of a drug remains unchanged during its passage through the body (Kasprzyk-Hordern et al., 2007; Winkler et al., 2008). Phase I metabolism adds polar groups to the molecular framework. This increases aqueous solubility and allows excretion in urine. Metabolites can sometimes be found in greater concentration in environmental waters than the original drug. The main form of sulphamethoxazole in raw influent water is its metabolite N-acetylsulfamethoxazole (Göbel et al., 2007). Metabolites usually have lower physiological activity than the parent drug, though for paracetamol a minor metabolite is the compound responsible for its toxic effects. Phase II metabolism forms conjugates in which the drug is coupled with a hydrophilic side-group. Paracetamol forms sulphate and glucuronide conjugates (Moffat et al., 2004). Conjugation again increases the water solubility. It is possible for conjugates to break down during sewage treatment to regenerate the original drug and so increase its concentration in the effluent (Roberts and Thomas, 2006).

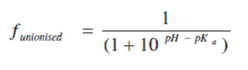

Physicochemical properties. The majority of drugs are either weak acids or weak bases. Because many of these compounds have a dissociation constant (pKa) value in the region of 4-9 (Jones et al., 2002), the ionisation of drugs will differ significantly in aqueous environments which have different pH values. Typically soft water has a pH of 5.5-7.0, hard water 7-8 and sea water 7.5-8.4. For an acid, the fraction remaining unionised, funionised, can be calculated by

Typical solubilities of the unionised forms are in the low mg L-1 range. The ionised form will have much higher solubility.

One of the mechanisms for pharmaceutical removal in sewage treatment is the sorption of hydrophobic or insoluble material onto solids and so will be pH dependent.

The octanol/water partition coefficient, Kow, is used to estimate the bioconcentration of pollutants (Chiou et al., 1977) or sorption of neutral organic compounds onto solid material (Jones et al., 2005). Modification of Kow to account for partial ionisation leads to a prediction of pH dependence of bioconcentration and sorption.

The octanol/water partition coefficient, Kow, is used to estimate the bioconcentration of pollutants (Chiou et al., 1977) or sorption of neutral organic compounds onto solid material (Jones et al., 2005). Modification of Kow to account for partial ionisation leads to a prediction of pH dependence of bioconcentration and sorption.

However, this approach was developed for non-polar pollutants, (e.g. p,p′–DDT, dioxins, PCBs), which partition by hydrophobic interaction. Even the neutral forms of drugs can be highly polar, leading to electrostatic and other interactions with solids (Radjenović et al., 2009) and this may not have been taken into consideration in simple models.

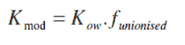

Pharmaceuticals are often classified according to their therapeutic action. Representative pharmaceuticals are shown in Figure 1 together with dissociation constant and octanol/water partition coefficient data.

Pharmaceuticals are often classified according to their therapeutic action. Representative pharmaceuticals are shown in Figure 1 together with dissociation constant and octanol/water partition coefficient data.

Many pharmaceuticals have chiral centres, and therapeutic activity is enantiomer-specific.

The enantiomeric ratio of a drug may change in the environment and during sewage treatment (Buser et al., 1999; Matamoros et al., 2009), altering its potential effect on organisms.

Most pharmaceuticals contain aromatic groups which absorb UV radiation. Ozone will attack any carbon-carbon multiple bond. UV photolysis and ozonolysis are two methods for degrading pharmaceuticals and are often used in tertiary sewage treatment.

The enantiomeric ratio of a drug may change in the environment and during sewage treatment (Buser et al., 1999; Matamoros et al., 2009), altering its potential effect on organisms.

Most pharmaceuticals contain aromatic groups which absorb UV radiation. Ozone will attack any carbon-carbon multiple bond. UV photolysis and ozonolysis are two methods for degrading pharmaceuticals and are often used in tertiary sewage treatment.

Sewage treatment

Pharmaceuticals and their metabolites are predominantly excreted in urine though they may also be present in faeces (Winkler et al., 2008). Input concentrations to sewage treatment plants are usually less than 1-2 mg L-1 with higher concentrations for more common drugs such as paracetamol (Miège et al., 2009). Sewage treatment processes are graded as primary, secondary and tertiary treatment. Most sewage plants have primary and secondary treatment. Tertiary treatment is usually a method for the removal of contaminants which are specific to a given location.

Pharmaceuticals and their metabolites are predominantly excreted in urine though they may also be present in faeces (Winkler et al., 2008). Input concentrations to sewage treatment plants are usually less than 1-2 mg L-1 with higher concentrations for more common drugs such as paracetamol (Miège et al., 2009). Sewage treatment processes are graded as primary, secondary and tertiary treatment. Most sewage plants have primary and secondary treatment. Tertiary treatment is usually a method for the removal of contaminants which are specific to a given location.

The aim of sewage treatment is to produce an effluent with as low an organic content as possible, a low suspended-solid content and with pathogenic micro-organisms removed. Discharge concentrations may be set for individual chemicals. Sewage sludge is produced as a waste and is commonly disposed by landfill or is spread on land as a soil conditioner. Both can be additional routes for the pharmaceuticals to re-enter the environment.

Two operating parameters have been found useful for plant comparison: hydraulic retention time (HRT) and solids retention time (SRT). An accurate estimation of HRT is also necessary in the experimental determination of removal efficiencies (Zorita et al., 2009) as input and effluent samples need to be matched. Terzic et al. (2008) have suggested that some results showing increases in concentration during treatment processes may be due to sampling inaccuracy.

Two operating parameters have been found useful for plant comparison: hydraulic retention time (HRT) and solids retention time (SRT). An accurate estimation of HRT is also necessary in the experimental determination of removal efficiencies (Zorita et al., 2009) as input and effluent samples need to be matched. Terzic et al. (2008) have suggested that some results showing increases in concentration during treatment processes may be due to sampling inaccuracy.

Primary treatment

This is the removal of floating and suspended solids such as wood, paper and faecal matter, which would disrupt later stages of the treatment, and comprises screening and sedimentation. Hydrated lime, aluminium sulphate or iron salts may be added to promote the sedimentation. One investigation indicated that drug concentrations are lowered during primary treatment and by implication are removed with the solid matter (Zorita et al., 2009). This was correlated with their low Kow. However, no elimination was found for sulfonamides, macrolides and trimethoprim (Göbel et al., 2007) or for a range of anti-microbials (Peng et al., 2006).

Secondary treatment

Organic material is degraded under aerobic conditions using populations of micro-organisms incorporated into activated sludge and/or membrane bioreactors. Loss of pharmaceuticals can be either by degradation or sorption onto sewage sludge. Santos et al. (2005) studied four sewage plants with primary and activated sludge secondary treatment: 90% removal was achieved for ibuprofen, ca. 60% for naproxen but below 26% for carbamezapine. Peng et al. (2006) found that activated sludge could remove > 85% of several antimicrobials. Poor removal was found for naproxen and ketoprofen, both amide-type pharmaceuticals (Nakada et al., 2006). A plant with primary treatment, activated sewage sludge, and final clarification (Gómez et al., 2007) showed >70% removal for a wide range of drugs except diclofenac (59%) and carbamezapine (20%). Carballa et al. (2007) found no elimination of carbamezapine.

This is the removal of floating and suspended solids such as wood, paper and faecal matter, which would disrupt later stages of the treatment, and comprises screening and sedimentation. Hydrated lime, aluminium sulphate or iron salts may be added to promote the sedimentation. One investigation indicated that drug concentrations are lowered during primary treatment and by implication are removed with the solid matter (Zorita et al., 2009). This was correlated with their low Kow. However, no elimination was found for sulfonamides, macrolides and trimethoprim (Göbel et al., 2007) or for a range of anti-microbials (Peng et al., 2006).

Secondary treatment

Organic material is degraded under aerobic conditions using populations of micro-organisms incorporated into activated sludge and/or membrane bioreactors. Loss of pharmaceuticals can be either by degradation or sorption onto sewage sludge. Santos et al. (2005) studied four sewage plants with primary and activated sludge secondary treatment: 90% removal was achieved for ibuprofen, ca. 60% for naproxen but below 26% for carbamezapine. Peng et al. (2006) found that activated sludge could remove > 85% of several antimicrobials. Poor removal was found for naproxen and ketoprofen, both amide-type pharmaceuticals (Nakada et al., 2006). A plant with primary treatment, activated sewage sludge, and final clarification (Gómez et al., 2007) showed >70% removal for a wide range of drugs except diclofenac (59%) and carbamezapine (20%). Carballa et al. (2007) found no elimination of carbamezapine.

Joss et al. (2006) investigated the action of activated sewage sludge and membrane bioreactors in batch experiments. Pharmaceuticals were grouped according to the first-order degradation rate constants derived from this study. The results broadly correlated with results from sewage plants, and showed a low rate for diclofenac. The highest rate was for paracetamol. Non-correlation was attributed to the presence of conjugates. Implications are that dilution of the input stream (e.g. by rainwater) would lower the degradation rate, and that treatment in small compartments rather than a single large compartment would improve the degradation. Increased HRT would also increase degradation. Choi et al. (2008) studied four sewage plants with activated sludge treatment over a range of flow and input concentrations. Cimetidine, sulphamethoxazole and carbamezapine were poorly removed under all conditions.

Maurer et al. (2007) compared batch experiments for the removal of β-blockers with results from two sewage treatment plants. The performance improved with increasing HRT, and the elimination appeared to be by biological degradation rather than sorption onto sewage sludge. Sorption coefficients did not correlate with Kow. This was attributed to ionic interactions with the solid. Jones et al. (2007) studied an activated-sludge plant with nitrifying and denitrifying zones. Elimination rates were ca. 90% for ibuprofen, paracetamol, salnutamol and methanamic acid. Mass balances indicated removal by biological degradation rather than sorption onto the sewage sludge. Gulkowska et al. (2008) compared plants with primary and secondary treatment and chemically-enhanced primary treatment for antibiotic removal. The highest removal efficiencies were with antibiotics, which were readily adsorbed onto particulate matter. Increased HRT appeared to increase the removal efficiency.

Terzic et al. (2008) gave a summary of the behaviour of pharmaceuticals in over 70 wastewater treatment plants and a detailed study of one plant biological treatment plant. Effluent concentrations exceeded input concentrations for atenelol, diclofenac, trimethoprym, arithromyan and erythromycin, and only ibuprofen had >95% removal efficiency. Increasing concentrations of propranolol, tamoxifen and methanamic acid have been found by Roberts and Thomas (2006). Radjenović et al. (2009) compared the removal of conventional activated sludge with pilot-plant advanced-membrane bioreactor treatment. Enhanced removal was found for most drugs with the membrane bioreactor, but carbamezapine and hydrodichlorothiazide had less than 10% removal in each process. Twenty out of the twenty-six pharmaceuticals were detected in the sewage sludge.

Several recent papers have investigated specific pharmaceuticals which cause problems or those which have not been given much attention: Zhang et al. (2008); Stülten et al. (2008); Leclerq et al. (2009); Scheurer et al. (2009).

Miège et al. (2009) have compiled a database of removal efficiencies of plants with primary and secondary treatment. Statistical analysis indicated that activated sludge with nitrogen treatment and membrane bioreactors were the most efficient. The KNAPPE project, part of the EU Sixth Framework Programme (Touraud, E., 2008) concluded that the secondary treatment plant design is not a major factor. More important considerations are operating parameters such as SRT and HRT.

Maurer et al. (2007) compared batch experiments for the removal of β-blockers with results from two sewage treatment plants. The performance improved with increasing HRT, and the elimination appeared to be by biological degradation rather than sorption onto sewage sludge. Sorption coefficients did not correlate with Kow. This was attributed to ionic interactions with the solid. Jones et al. (2007) studied an activated-sludge plant with nitrifying and denitrifying zones. Elimination rates were ca. 90% for ibuprofen, paracetamol, salnutamol and methanamic acid. Mass balances indicated removal by biological degradation rather than sorption onto the sewage sludge. Gulkowska et al. (2008) compared plants with primary and secondary treatment and chemically-enhanced primary treatment for antibiotic removal. The highest removal efficiencies were with antibiotics, which were readily adsorbed onto particulate matter. Increased HRT appeared to increase the removal efficiency.

Terzic et al. (2008) gave a summary of the behaviour of pharmaceuticals in over 70 wastewater treatment plants and a detailed study of one plant biological treatment plant. Effluent concentrations exceeded input concentrations for atenelol, diclofenac, trimethoprym, arithromyan and erythromycin, and only ibuprofen had >95% removal efficiency. Increasing concentrations of propranolol, tamoxifen and methanamic acid have been found by Roberts and Thomas (2006). Radjenović et al. (2009) compared the removal of conventional activated sludge with pilot-plant advanced-membrane bioreactor treatment. Enhanced removal was found for most drugs with the membrane bioreactor, but carbamezapine and hydrodichlorothiazide had less than 10% removal in each process. Twenty out of the twenty-six pharmaceuticals were detected in the sewage sludge.

Several recent papers have investigated specific pharmaceuticals which cause problems or those which have not been given much attention: Zhang et al. (2008); Stülten et al. (2008); Leclerq et al. (2009); Scheurer et al. (2009).

Miège et al. (2009) have compiled a database of removal efficiencies of plants with primary and secondary treatment. Statistical analysis indicated that activated sludge with nitrogen treatment and membrane bioreactors were the most efficient. The KNAPPE project, part of the EU Sixth Framework Programme (Touraud, E., 2008) concluded that the secondary treatment plant design is not a major factor. More important considerations are operating parameters such as SRT and HRT.

Tertiary treatment

Disinfection either by UV, chlorination or ozonolysis is the most common tertiary-treatment process. The plants may not be operated continuously. Northumbria Water (UK) has applied to turn off UV treatment on six of its plants outside the bathing/watersport season (Environment Agency, 2008). Chlorination of the treatment plant on the River Rakkolanjoki (Finland) is only applied May –September (Vieno et al., 2007). Klavarioti et al. (2009) reviewed laboratory or pilot-plant scale disinfection methods alongside these current processes. Other tertiary-treatment processes include phosphate removal and sand filtration (Göbel et al., 2007; Zorita et al., 2009), and sewage application to land (Gielen et al., 2009).

UV treatment. 254 nm mercury lamps are used. Other wastewater components can absorb the radiation, and the radiation may not be able to penetrate solids. Roberts and Thomas (2006) found that during UV tertiary treatment there was a decrease in concentration of all pharmaceuticals studied except for erythromycin, the only compound without a UV-absorbing aromatic ring. The maximum removal efficiency was ca. 70%. However, UV treatment may not completely destroy the molecular framework. Miao et al. (2005) found an increase in concentration of carbamezapine metabolites, possibly due to conjugate destruction. Kim et al. (2009) compared UV and UV/H2O2 treatment. Increased destruction was found with UV/ H2O2 for all pharmaceuticals including erythromycin. Earlier work had shown similar improved destruction of carbamezapine. Laboratory studies by Yuan et al. (2009) showed improvement for ibuprofen, diphenylhydramine, phenazone and phenytoin.

Chlorination. Vieno et al. (2007) have compared plants with primary, secondary and a range of tertiary treatment including coagulation, chlorination and polymer addition (HRT 1.5-17.5 hr). Carbamezapine was not removed, whereas > 85% fluoroquinolines were eliminated. Four treatment plants with different technologies (conventional sewage sludge, oxidation ditches, bioreactors with UV treatment and chlorination, lagoons) have been studied by Ying et al. (2009). Biodegradation seems the main mechanism rather than sorption onto sludge. There was little removal of diclofenac in any of the processes. Xu et al. (2007) studied antibiotics in four plants with UV, chlorine and no disinfection. The least effective was the plant with no disinfection. In contrast to removal mechanisms for most other pharmaceuticals, the removal of hydrophobic fluoroquinolines was attributed to absorption on sewage sludge.

Ozonation. Nakada et al. (2007) have studied the effect of ozonation in combination with sand filtration, and correlated the removal efficiency with chemical structure. Compounds with a double bond or aromatic ring were readily removed (over the whole treatment process > 80%), whereas compounds with amide structures (e.g. carbamezapine, diethyltoluamide) were resistant. Sand filtration had a variable effect but appeared to correlate with drug hydrophobicity.

Sludge disposal

Over 8.1 million tons of sewage sludge are produced in the EU each year; 21% is disposed of on land in Sweden (Eriksonn et al., 2008) and 65% in Spain (Carbonell et al., 2009). 35-45% is disposed as landfill (Touraud, 2008). There has long been concern over the possibility of heavy metals re-entering the food chain from sewage sludge application, and of the presence of pathogenic micro-organisms. This concern now includes pharmaceuticals. Drainage from sewage sludge in landfill can contaminate groundwater. Díaz-Cruz et al. (2003) have summarised the behaviour of drugs in soils, sediments and sludge. Eriksson et al. (2008) found twenty pharmaceuticals in sewage sludge with 128 others potentially being present. Typical concentrations found are in the ng g-1 range (Barron et al., 2008; Sponberg and Witter 2008, Radjenović et al., 2009). After application to soil, there is evidence of degradation, but successive re-application could increase drug concentrations significantly. A recent comprehensive review of organic contaminants in sewage sludge (Smith, 2009) has concluded that the main concern for pharmaceuticals in the environment is the development of antibiotic resistance in soil bacteria.

Topp et al. (2008) have studied surface run-off following surface application and sub-surface injection of biosolids. Subsurface application effectively eliminates surface run-off. Edwards et al. (2009) studied the effect of biosolids applied to land and their concentrations in tile drainage systems (removing excess water from the soil subsurface). Carbamazapine, sufamethoxazole and naproxen were detected in the drainage water. Sabourin et al. (2009) investigated the transport potential in surface run-off, correlating this with Kow. Pharmaceuticals which with log Kow < 2.45 were readily mobilised and those with log Kow > 3.18 had little transport potential. Kinney et al. (2008) have studied the uptake into earthworms in a field treated with biosolids. Carbamezapine was detectable in the original bio-solid but could not be detected in the treated soil or in the earthworms.

Summary

There is some correlation of drug degradation rates with their physicochemical properties. But differences in performance of individual sewage plants (operating factors HRT and SRT, and plant design) need to be taken into consideration. A high hydraulic retention time, and a plant design which encourages a diversity of bio-organisms, promote the efficient removal of drugs. There is also an increasing awareness of the need for tertiary treatment.

A wide range of pharmaceuticals is used medicinally. Hence no single sewage treatment method is suitable for all drugs. A number of individual drugs, e.g. carbamezapine and diclofenac, appear to have low removal efficiencies in primary and secondary treatment regardless of plant design. UV treatment is effective for a large number of pharmaceuticals; addition of H2O2 shows promise for increasing rates of degradation. Although loss by adsorption on sludge appears to be a minor factor in the removal of many pharmaceuticals in sewage treatment, increased use of sewage sludge as a soil conditioner is an additional route for pharmaceuticals to contaminate soil, with further leaching into groundwater.

References

Aga, D.S. (ed.) (2008), Fate of Pharmaceuticals in the Environment and in Water Treatment Systems, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fl.

Barron, L.; Tobin, J.; Paull, B. (2008), ‘Multi-residue determination of pharmaceuticals in sludge and sludge enriched soils using pressurised liquid extraction, solid phase extraction and liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry’, J. Environ. Monitor., 10, 353-361.

Bolong, N.; Ismail, A. F.; Salim, M. R.; Matsuura, T. (2009), ‘A review of the effects of emerging contaminants in wastewater and options for their removal’, Desalination, 239, 229-246.

Bottoms, M.J. (2009), ‘Veterinary antibiotics in the terrestrial environment’, RSC Environmental Chemistry Group Bulletin, July 2009, 15-20

Buser, H-R.; Poiger, T.; Müller, M. D. (1999), ‘Occurrence and environmental behaviour of the chiral pharmaceutical drug ibuprofen in surface waters and wastewater’, Environ. Sci. Technol. 33, 2529-2535.

Carballa, M.; Omil, F.; Ternes, T.; Lema, J. M. (2007), ‘Fate of pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs) during anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge’, Water Res., 41, 2139-2150.

Carbonell, G.; Pro, J. ; Gómez, N.; Babín, M. M.; Fernández, C.; Alonso, E.; Tarazona, J. V. (2009), ’Sewage sludge applied to agricultural soil: Ecotoxicological effects on representative soil organisms’, Ecotox. Environ. Safe., 72, 1309-1319.

Chiou, C. T.; Freed, V. H.; Schnedding, D. W.; Kohnert, R. L. (1977), ‘Partition coefficient and bioaccumulation of selected organic chemicals’, Environ. Sci. Technol. 11, 475-478.

Choi, K.; Kim, Y.; Park, J.; Park, C. K.; Kim, M. Y.; Kim, H. S.; Kim, P. (2008), ‘Seasonal variations of several pharmaceutical residues in surface water and sewage treatment plants of Han River, Korea’, Sci. Total Environ., 405, 120-128.

Díaz-Cruz, M. S.; López de Alda, M. J.; Barceló D. (2003), ‘Environmental behaviour and analysis of veterinary and human drugs in soils, sediments and sludge’, TRAC–Trend. Anal. Chem., 22, 340-351.

Drewes J. E. (2007), ‘Removal of pharmaceutical residues during wastewater treatment’, Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry, 50, 427-449, Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Edwards, M.; Topp, E.; Metcalfe, C. D.; Li, H.; Gottschall, N.; Bolton, P.; Curnoe, W. ; Payne, M.; Beck, A.; Kleywegt, S.; Lapen, D. R. (2009), ‘Pharmaceutical and personal care products in tile drainage following surface spreading and injection of dewatered municipal biosolids to an agricultural field’, Sci. Total Environ., 407, 4220-4230.

Environment Agency (2008), ‘UV sewage treatment on the north east coast’, http://www.environment-agency.gov.uk/homeandleisure/pollution/water/31418.aspx Accessed 1/12/09.Eriksson, E.; Christensen, N.; Schmidt, J. E.; Ledin, A. (2008), ‘Potential priority pollutants in sewage sludge’, Desalination, 226, 371-388.Gielen, G.J.H.P.; van den Heuvel, M.R.; Clinton, P.W.; Greenfield, L.G.(2009), ‘Factors impacting on pharmaceutical leaching following sewage application to land’, Chemosphere, 74, 537-542.Göbel, A.; McArdell, C. S.; Joss, A.; Siegrist, H.; Giger, W. (2007), ‘Fate of sulfonamides, macrolides, and trimethoprim in different wastewater treatment technologies’ Sci. Total Environ., 372, 361-371.

Gómez, M. J.; Martínez Bueno, M. J.; Lacorte, S.; Fernández-Alba, A. R; Agüera, A. (2007), ‘Pilot survey monitoring pharmaceuticals and related compounds in a sewage treatment plant located on the Mediterranean coast’, Chemosphere, 66, 993-1002.

Gulkowska, A.; Leung, H. W.; So, M. K ; Taniyasu, S.; Yamashita, N.; Yeung, L. W. Y ; Richardson, B. J; Lei, A. P.; Giesy, J. P.; Lam P. K. S. (2008), ‘Removal of antibiotics from wastewater by sewage treatment facilities in Hong Kong and Shenzhen, China’, Water Res., 42, 395-403.

Heberer, T. (2002), ‘Occurrence, fate and removal of pharmaceutical residues in the aquatic environment: a review of recent research data’, Toxicol Lett., 131, 5-17.

Hill, E.; Tyler, C.R. (2005), ‘Endocrine disruption and UK river fish stocks’, RSC Environmental Chemistry Group Bulletin, January 2005, 4-6

Jones, O. A. H.; Voulvoulis, N.; Lester, J. N. (2002), ‘Aquatic environmental assessment of the top 25 English prescription pharmaceuticals’, Water Res., 36, 5013-5022.

Jones, O. A.H.; Voulvoulis, N.; Lester, J. N. (2005), ‘Human pharmaceuticals in wastewater treatment processes’, Crit. Rev. Env. Sci. Tec., 35, 401-427

Jones, O. A. H.; Voulvoulis, N; Lester, J. N. (2007), ‘ The occurrence and removal of selected pharmaceutical compounds in a sewage treatment works utilising activated sludge treatment’, Environ. Pollut., 145, 738-744.

Joss, A.; Zabczynski, S.; Göbel, A.; Hoffmann, B.; Löffler, D.; McArdell, C. S.; Ternes, T. A.; Angela Thomsen, A.; Siegrist, H. (2006), ‘Biological degradation of pharmaceuticals in municipal wastewater treatment: Proposing a classification scheme’, Water Res., 40, 1686-1696.

Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Dinsdale, R. M.; Guwy, A. J. (2007), ‘Multi-residue method for the determination of basic/neutral pharmaceuticals and illicit drugs in surface water by solid-phase extraction and ultra-performance liquid chromatography-positive electrospray ionisation tandem mass spectrometry’, J. Chromatogr. A, 1161, 132-145.

Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Dinsdale, R. M.; Guwy, A. J. (2008), ‘The occurrence of pharmaceuticals, personal care products, endocrine disruptors and illicit drugs in surface water in South Wales, UK’, Water Res., 42, 3498-3518.

Kim, I.; Yamashita, N.; Tanaka, H (2009), ‘Performance of UV and UV/H2O2 processes for the removal of pharmaceuticals detected in secondary effluent of a sewage treatment plant in Japan’, J. Hazard. Mater., 166, 1134-1140.

Kinney, C. A.; Furlong E. T.; Kolpin, D. W.; Burkhardt, M. R.; Zaugg S. D.; Werner, S. L.; Bossio, J. P.; Benotti, M. J. (2008), ‘Bioaccumulation of pharmaceuticals and other anthropogenic waste indicators in earthworms from agricultural soil amended with biosolid or swine manure’, Environ. Sci. Technol., 42, 1863-70.

Klavarioti, M.; Mantzavinos, D.; Kassinos, D. (2009), ‘Removal of residual pharmaceuticals from aqueous systems by advanced oxidation processes’, Environ. Int., 35, 402-417.

Kolpin, D. W.; Furlong, E. T.; Meyer, M. T.; Thurman, E. M; Zaug, S. D.; Barber, L. B. ; Buxton H. T. (2002), ‘Pharmaceuticals, hormones, and other organic wastewater contaminants in U.S. streams 1999-2000; a national reconnaissance’, Environ. Sci. Technol., 36, 1202-1211.

Leclerq, M.; Mathieu, O.; Gomez, E.; Casellas, C.; Fenet, H.; Hillaire-Buys, D. (2009), ‘Presence and fate of carbamezapine, oxcarbamezapine, and seven of their metabolites at wastewater treatment plants’, Arch. Environ. Cont. Tox., 56, 408-415.

Matamoros, V.; Hijosa, M.; Bayona J. M. (2009), ‘Assessment of the pharmaceutical active compounds removal in wastewater treatment systems at enantiomeric level. Ibuprofen and naproxen’, Chemosphere, 75, 200-205.

Maurer, M.; Escher, B. I.; Richle, P. ; Schaffner, C.; Alder, A. C. (2007), ‘Elimination of β-blockers in sewage treatment plants’, Water Res., 41, 1614-1622.

Miao, X-S; Yang, J-J; Metcalfe, C. D. (2005), ‘Carbamazepine and its metabolites in wastewater and in biosolids in a municipal wastewater treatment plant’, Environ. Sci. and Technol., 39, 7469–7475.

Miège, C.; Choubert, J. M.; Ribeiro, L.; Eusèbe, M.; Coquery, M. (2009),‘Fate of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in wastewater treatment plants – Conception of a database and first results’, Environ. Pollut., 157, 1721-1726.

Moffat, A.C.; Ossleton, D.M.; Widdop, B.; Galichet, L.Y. (2004), Clarke’s Analysis of Drugs and Poisons , 3rd Ed, Pharmaceutical Press, London.

Nakada, N; Tanishima, T.; Shinohara, H.; Kiri, K.; Takada, H. (2006), ‘Pharmaceutical chemicals and endocrine disrupters in municipal wastewater in Tokyo and their removal during activated sludge treatment’, Water Res., 40, 3297-3303.

Nakada, N; Shinohara, H.; Murata, A.; Kiri, K.; Managaki, S; Sato, N.; Takada, H. (2007), ‘Removal of selected pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) and endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) during sand filtration and ozonation at a municipal sewage treatment plant’, Water Res., 41, 4373-4382.

Oaks, J.L.; Gilbert, M.; Virani, M.Z.; Watson, R.T.; Meteyer, C.U.; Rideout, B.A.; Shivaprasad, H.L.; Ahmed, S.; Chaudhry, M.J.; Arshad, M.; Mahmood, S.; Ali, A.; Khan, A.A. (2004), ‘Diclofenac residues as the cause of vulture population decline in Pakistan’, Nature, 427(6975), 630-633.

Peng, X.; Wang, Z; Kuang, W; Tan, J.; Li, K. (2006), ‘A preliminary study on the occurrence and behavior of sulfonamides, ofloxacin and chloramphenicol antimicrobials in wastewaters of two sewage treatment plants in Guangzhou, China’, Sci. Total Environ., 371, 314-322.

Radjenović, J.; Petrović, M.; Barceló, D. (2009), ‘Fate and distribution of pharmaceuticals in wastewater and sewage sludge of the conventional activated sludge (CAS) and advanced membrane bioreactor (MBR) treatment’, Water Res., 43, 831-841.

Roberts, P. H.; Thomas, K .V. (2006), ‘The occurrence of selected pharmaceuticals in wastewater effluent and surface waters of the lower Tyne catchment’, Sci. Total Environ., 356, 143-153.

Sabourin, L.; Andrew Beck, A.; Duenk, P. W.; Kleywegt, S.; Lapen, D. R.; Li, H.; Metcalfe, C. D.; Payne, M.; Topp, E. (2009), ‘Runoff of pharmaceuticals and personal care products following application of dewatered municipal biosolids to an agricultural field‘, Sci. Total Environ., 407, 4596-4604

Santos, J. L.; Aparicio, I; Alonso, E.; Callejón, M. (2005),‘Simultaneous determination of pharmaceutically active compounds in wastewater samples by solid phase extraction and high performance liquid chromatography with diode array and fluorescence detectors’, Anal. Chim. Acta, 550, 116-122.

Scheurer, M.; Sacher, F.; Brauch, H-J. (2009), ‘Occurrence of the antidiabetic drug metformin in sewage and surface waters in Germany’, J. Environ. Monitor., 11, 1608-1613.

Smith, S. R. (2009), ‘Organic contaminants in sewage sludge (biosolids) and their significance for agricultural recycling’, Philos. T. Roy. Soc. A , 367, 4005-4011.

Spongberg, A. L.; Witter, J. D. (2008), ‘Pharmaceutical compounds in the wastewater process stream in Northwest Ohio’, Sci. Total Environ., 397, 148-157.

Stülten, D; Zühlke, S; Lamshöft, M.; Spiteller, M. (2008), ‘Occurrence of diclofenac and selected metabolites in sewage effluents’, Sci. Total Environ., 405, 310-316.

Terzić, S.; Senta, I.; Ahel, M.; Gros, M.; Petrović, M; Barcelo, D.; Müller, J.; Knepper, T.; Martí, I.; Ventura, F.; Jovančić, P., Jabučar, D. (2008), ‘ Occurrence and fate of emerging wastewater contaminants in Western Balkan Region’, Sci. Total Environ., 399, 66-77.

Topp, E.; Monteiro, S. C.; Beck, A.; Coelho, B. B.; Boxall, A. B .A.; Duenk, P. W.; Kleywegt, S.; Lapen, D. R.; Payne, M.; Sabourin, L.; Li, H.; Metcalfe, C. D. (2008), ‘Runoff of pharmaceuticals and personal care products following application of biosolids to an agricultural field’, Sci. Total Environ., 396, 52-59.

Touraud, E. (2008), ‘D6.6 KNAPPE final report’, available online http://www.knappe-eu.org/fichiers/60-D6.6%20final%20report%20final.pdf. Accessed 1/12/09.

Vieno, N.; Tuhkanen, T.; Kronberg, L. (2007), ‘Elimination of pharmaceuticals in sewage treatment plants in Finland’, Water Res., 41, 1001-1012.

Winkler, M.; Faika, D.; Gulyas, H.; Otterpohl R. (2008) ‘A comparison of human pharmaceutical concentrations in raw municipal wastewater and yellow water’, Sci. Total Environ., 399, 96-104.

Xu, W. ; Zhang, G.; Li X., Zou, S.; Li, P.; Hu, Z.; Li, J. (2007), ‘Occurrence and elimination of antibiotics at four sewage treatment plants in the Pearl River Delta (PRD), South China’, Water Res., 41, 4526-4534.

Ying, G-G.; Kookana, R. S.; Kolpin, D. W. (2009), ‘Occurrence and removal of pharmaceutically active compounds in sewage treatment plants with different technologies’, J. Environ. Monitor., 11, 1498-1505.

Yuan, F.; Hu, C.; Hu, X.; Qu, J.; Yang, M.; (2009), ‘Degradation of selected pharmaceuticals in aqueous solution with UV and UV/H2O2’, Water Res., 43, 1766-1774.

Zhang, Y.; Geißen, S.-U.; Gal C. (2008), ‘Carbamazepine and diclofenac: Removal in wastewater treatment plants and occurrence in water bodies’, Chemosphere, 73, 1151-1161.

Zhou, J. H. ; Zhang, Z L. ; Banks, E. ; Grover, D. ; Jiang, J. Q. (2009), ‘Pharmaceutical residues in wastewater treatment works effluents and their impact on receiving water’ , J. Hazard. Mater., 166, 655-661.

Zorita, S.; Mårtensson, L.; Mathiasson, L.(2009), ‘Occurrence and removal of pharmaceuticals in a municipal sewage treatment system in the south of Sweden’, Sci. Total Environ., 407, 2760-2770.

Disinfection either by UV, chlorination or ozonolysis is the most common tertiary-treatment process. The plants may not be operated continuously. Northumbria Water (UK) has applied to turn off UV treatment on six of its plants outside the bathing/watersport season (Environment Agency, 2008). Chlorination of the treatment plant on the River Rakkolanjoki (Finland) is only applied May –September (Vieno et al., 2007). Klavarioti et al. (2009) reviewed laboratory or pilot-plant scale disinfection methods alongside these current processes. Other tertiary-treatment processes include phosphate removal and sand filtration (Göbel et al., 2007; Zorita et al., 2009), and sewage application to land (Gielen et al., 2009).

UV treatment. 254 nm mercury lamps are used. Other wastewater components can absorb the radiation, and the radiation may not be able to penetrate solids. Roberts and Thomas (2006) found that during UV tertiary treatment there was a decrease in concentration of all pharmaceuticals studied except for erythromycin, the only compound without a UV-absorbing aromatic ring. The maximum removal efficiency was ca. 70%. However, UV treatment may not completely destroy the molecular framework. Miao et al. (2005) found an increase in concentration of carbamezapine metabolites, possibly due to conjugate destruction. Kim et al. (2009) compared UV and UV/H2O2 treatment. Increased destruction was found with UV/ H2O2 for all pharmaceuticals including erythromycin. Earlier work had shown similar improved destruction of carbamezapine. Laboratory studies by Yuan et al. (2009) showed improvement for ibuprofen, diphenylhydramine, phenazone and phenytoin.

Chlorination. Vieno et al. (2007) have compared plants with primary, secondary and a range of tertiary treatment including coagulation, chlorination and polymer addition (HRT 1.5-17.5 hr). Carbamezapine was not removed, whereas > 85% fluoroquinolines were eliminated. Four treatment plants with different technologies (conventional sewage sludge, oxidation ditches, bioreactors with UV treatment and chlorination, lagoons) have been studied by Ying et al. (2009). Biodegradation seems the main mechanism rather than sorption onto sludge. There was little removal of diclofenac in any of the processes. Xu et al. (2007) studied antibiotics in four plants with UV, chlorine and no disinfection. The least effective was the plant with no disinfection. In contrast to removal mechanisms for most other pharmaceuticals, the removal of hydrophobic fluoroquinolines was attributed to absorption on sewage sludge.

Ozonation. Nakada et al. (2007) have studied the effect of ozonation in combination with sand filtration, and correlated the removal efficiency with chemical structure. Compounds with a double bond or aromatic ring were readily removed (over the whole treatment process > 80%), whereas compounds with amide structures (e.g. carbamezapine, diethyltoluamide) were resistant. Sand filtration had a variable effect but appeared to correlate with drug hydrophobicity.

Sludge disposal

Over 8.1 million tons of sewage sludge are produced in the EU each year; 21% is disposed of on land in Sweden (Eriksonn et al., 2008) and 65% in Spain (Carbonell et al., 2009). 35-45% is disposed as landfill (Touraud, 2008). There has long been concern over the possibility of heavy metals re-entering the food chain from sewage sludge application, and of the presence of pathogenic micro-organisms. This concern now includes pharmaceuticals. Drainage from sewage sludge in landfill can contaminate groundwater. Díaz-Cruz et al. (2003) have summarised the behaviour of drugs in soils, sediments and sludge. Eriksson et al. (2008) found twenty pharmaceuticals in sewage sludge with 128 others potentially being present. Typical concentrations found are in the ng g-1 range (Barron et al., 2008; Sponberg and Witter 2008, Radjenović et al., 2009). After application to soil, there is evidence of degradation, but successive re-application could increase drug concentrations significantly. A recent comprehensive review of organic contaminants in sewage sludge (Smith, 2009) has concluded that the main concern for pharmaceuticals in the environment is the development of antibiotic resistance in soil bacteria.

Topp et al. (2008) have studied surface run-off following surface application and sub-surface injection of biosolids. Subsurface application effectively eliminates surface run-off. Edwards et al. (2009) studied the effect of biosolids applied to land and their concentrations in tile drainage systems (removing excess water from the soil subsurface). Carbamazapine, sufamethoxazole and naproxen were detected in the drainage water. Sabourin et al. (2009) investigated the transport potential in surface run-off, correlating this with Kow. Pharmaceuticals which with log Kow < 2.45 were readily mobilised and those with log Kow > 3.18 had little transport potential. Kinney et al. (2008) have studied the uptake into earthworms in a field treated with biosolids. Carbamezapine was detectable in the original bio-solid but could not be detected in the treated soil or in the earthworms.

Summary

There is some correlation of drug degradation rates with their physicochemical properties. But differences in performance of individual sewage plants (operating factors HRT and SRT, and plant design) need to be taken into consideration. A high hydraulic retention time, and a plant design which encourages a diversity of bio-organisms, promote the efficient removal of drugs. There is also an increasing awareness of the need for tertiary treatment.

A wide range of pharmaceuticals is used medicinally. Hence no single sewage treatment method is suitable for all drugs. A number of individual drugs, e.g. carbamezapine and diclofenac, appear to have low removal efficiencies in primary and secondary treatment regardless of plant design. UV treatment is effective for a large number of pharmaceuticals; addition of H2O2 shows promise for increasing rates of degradation. Although loss by adsorption on sludge appears to be a minor factor in the removal of many pharmaceuticals in sewage treatment, increased use of sewage sludge as a soil conditioner is an additional route for pharmaceuticals to contaminate soil, with further leaching into groundwater.

References

Aga, D.S. (ed.) (2008), Fate of Pharmaceuticals in the Environment and in Water Treatment Systems, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fl.

Barron, L.; Tobin, J.; Paull, B. (2008), ‘Multi-residue determination of pharmaceuticals in sludge and sludge enriched soils using pressurised liquid extraction, solid phase extraction and liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry’, J. Environ. Monitor., 10, 353-361.

Bolong, N.; Ismail, A. F.; Salim, M. R.; Matsuura, T. (2009), ‘A review of the effects of emerging contaminants in wastewater and options for their removal’, Desalination, 239, 229-246.

Bottoms, M.J. (2009), ‘Veterinary antibiotics in the terrestrial environment’, RSC Environmental Chemistry Group Bulletin, July 2009, 15-20

Buser, H-R.; Poiger, T.; Müller, M. D. (1999), ‘Occurrence and environmental behaviour of the chiral pharmaceutical drug ibuprofen in surface waters and wastewater’, Environ. Sci. Technol. 33, 2529-2535.

Carballa, M.; Omil, F.; Ternes, T.; Lema, J. M. (2007), ‘Fate of pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs) during anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge’, Water Res., 41, 2139-2150.

Carbonell, G.; Pro, J. ; Gómez, N.; Babín, M. M.; Fernández, C.; Alonso, E.; Tarazona, J. V. (2009), ’Sewage sludge applied to agricultural soil: Ecotoxicological effects on representative soil organisms’, Ecotox. Environ. Safe., 72, 1309-1319.

Chiou, C. T.; Freed, V. H.; Schnedding, D. W.; Kohnert, R. L. (1977), ‘Partition coefficient and bioaccumulation of selected organic chemicals’, Environ. Sci. Technol. 11, 475-478.

Choi, K.; Kim, Y.; Park, J.; Park, C. K.; Kim, M. Y.; Kim, H. S.; Kim, P. (2008), ‘Seasonal variations of several pharmaceutical residues in surface water and sewage treatment plants of Han River, Korea’, Sci. Total Environ., 405, 120-128.

Díaz-Cruz, M. S.; López de Alda, M. J.; Barceló D. (2003), ‘Environmental behaviour and analysis of veterinary and human drugs in soils, sediments and sludge’, TRAC–Trend. Anal. Chem., 22, 340-351.

Drewes J. E. (2007), ‘Removal of pharmaceutical residues during wastewater treatment’, Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry, 50, 427-449, Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Edwards, M.; Topp, E.; Metcalfe, C. D.; Li, H.; Gottschall, N.; Bolton, P.; Curnoe, W. ; Payne, M.; Beck, A.; Kleywegt, S.; Lapen, D. R. (2009), ‘Pharmaceutical and personal care products in tile drainage following surface spreading and injection of dewatered municipal biosolids to an agricultural field’, Sci. Total Environ., 407, 4220-4230.

Environment Agency (2008), ‘UV sewage treatment on the north east coast’, http://www.environment-agency.gov.uk/homeandleisure/pollution/water/31418.aspx Accessed 1/12/09.Eriksson, E.; Christensen, N.; Schmidt, J. E.; Ledin, A. (2008), ‘Potential priority pollutants in sewage sludge’, Desalination, 226, 371-388.Gielen, G.J.H.P.; van den Heuvel, M.R.; Clinton, P.W.; Greenfield, L.G.(2009), ‘Factors impacting on pharmaceutical leaching following sewage application to land’, Chemosphere, 74, 537-542.Göbel, A.; McArdell, C. S.; Joss, A.; Siegrist, H.; Giger, W. (2007), ‘Fate of sulfonamides, macrolides, and trimethoprim in different wastewater treatment technologies’ Sci. Total Environ., 372, 361-371.

Gómez, M. J.; Martínez Bueno, M. J.; Lacorte, S.; Fernández-Alba, A. R; Agüera, A. (2007), ‘Pilot survey monitoring pharmaceuticals and related compounds in a sewage treatment plant located on the Mediterranean coast’, Chemosphere, 66, 993-1002.

Gulkowska, A.; Leung, H. W.; So, M. K ; Taniyasu, S.; Yamashita, N.; Yeung, L. W. Y ; Richardson, B. J; Lei, A. P.; Giesy, J. P.; Lam P. K. S. (2008), ‘Removal of antibiotics from wastewater by sewage treatment facilities in Hong Kong and Shenzhen, China’, Water Res., 42, 395-403.

Heberer, T. (2002), ‘Occurrence, fate and removal of pharmaceutical residues in the aquatic environment: a review of recent research data’, Toxicol Lett., 131, 5-17.

Hill, E.; Tyler, C.R. (2005), ‘Endocrine disruption and UK river fish stocks’, RSC Environmental Chemistry Group Bulletin, January 2005, 4-6

Jones, O. A. H.; Voulvoulis, N.; Lester, J. N. (2002), ‘Aquatic environmental assessment of the top 25 English prescription pharmaceuticals’, Water Res., 36, 5013-5022.

Jones, O. A.H.; Voulvoulis, N.; Lester, J. N. (2005), ‘Human pharmaceuticals in wastewater treatment processes’, Crit. Rev. Env. Sci. Tec., 35, 401-427

Jones, O. A. H.; Voulvoulis, N; Lester, J. N. (2007), ‘ The occurrence and removal of selected pharmaceutical compounds in a sewage treatment works utilising activated sludge treatment’, Environ. Pollut., 145, 738-744.

Joss, A.; Zabczynski, S.; Göbel, A.; Hoffmann, B.; Löffler, D.; McArdell, C. S.; Ternes, T. A.; Angela Thomsen, A.; Siegrist, H. (2006), ‘Biological degradation of pharmaceuticals in municipal wastewater treatment: Proposing a classification scheme’, Water Res., 40, 1686-1696.

Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Dinsdale, R. M.; Guwy, A. J. (2007), ‘Multi-residue method for the determination of basic/neutral pharmaceuticals and illicit drugs in surface water by solid-phase extraction and ultra-performance liquid chromatography-positive electrospray ionisation tandem mass spectrometry’, J. Chromatogr. A, 1161, 132-145.

Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Dinsdale, R. M.; Guwy, A. J. (2008), ‘The occurrence of pharmaceuticals, personal care products, endocrine disruptors and illicit drugs in surface water in South Wales, UK’, Water Res., 42, 3498-3518.

Kim, I.; Yamashita, N.; Tanaka, H (2009), ‘Performance of UV and UV/H2O2 processes for the removal of pharmaceuticals detected in secondary effluent of a sewage treatment plant in Japan’, J. Hazard. Mater., 166, 1134-1140.

Kinney, C. A.; Furlong E. T.; Kolpin, D. W.; Burkhardt, M. R.; Zaugg S. D.; Werner, S. L.; Bossio, J. P.; Benotti, M. J. (2008), ‘Bioaccumulation of pharmaceuticals and other anthropogenic waste indicators in earthworms from agricultural soil amended with biosolid or swine manure’, Environ. Sci. Technol., 42, 1863-70.

Klavarioti, M.; Mantzavinos, D.; Kassinos, D. (2009), ‘Removal of residual pharmaceuticals from aqueous systems by advanced oxidation processes’, Environ. Int., 35, 402-417.

Kolpin, D. W.; Furlong, E. T.; Meyer, M. T.; Thurman, E. M; Zaug, S. D.; Barber, L. B. ; Buxton H. T. (2002), ‘Pharmaceuticals, hormones, and other organic wastewater contaminants in U.S. streams 1999-2000; a national reconnaissance’, Environ. Sci. Technol., 36, 1202-1211.

Leclerq, M.; Mathieu, O.; Gomez, E.; Casellas, C.; Fenet, H.; Hillaire-Buys, D. (2009), ‘Presence and fate of carbamezapine, oxcarbamezapine, and seven of their metabolites at wastewater treatment plants’, Arch. Environ. Cont. Tox., 56, 408-415.

Matamoros, V.; Hijosa, M.; Bayona J. M. (2009), ‘Assessment of the pharmaceutical active compounds removal in wastewater treatment systems at enantiomeric level. Ibuprofen and naproxen’, Chemosphere, 75, 200-205.

Maurer, M.; Escher, B. I.; Richle, P. ; Schaffner, C.; Alder, A. C. (2007), ‘Elimination of β-blockers in sewage treatment plants’, Water Res., 41, 1614-1622.

Miao, X-S; Yang, J-J; Metcalfe, C. D. (2005), ‘Carbamazepine and its metabolites in wastewater and in biosolids in a municipal wastewater treatment plant’, Environ. Sci. and Technol., 39, 7469–7475.

Miège, C.; Choubert, J. M.; Ribeiro, L.; Eusèbe, M.; Coquery, M. (2009),‘Fate of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in wastewater treatment plants – Conception of a database and first results’, Environ. Pollut., 157, 1721-1726.

Moffat, A.C.; Ossleton, D.M.; Widdop, B.; Galichet, L.Y. (2004), Clarke’s Analysis of Drugs and Poisons , 3rd Ed, Pharmaceutical Press, London.

Nakada, N; Tanishima, T.; Shinohara, H.; Kiri, K.; Takada, H. (2006), ‘Pharmaceutical chemicals and endocrine disrupters in municipal wastewater in Tokyo and their removal during activated sludge treatment’, Water Res., 40, 3297-3303.

Nakada, N; Shinohara, H.; Murata, A.; Kiri, K.; Managaki, S; Sato, N.; Takada, H. (2007), ‘Removal of selected pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) and endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) during sand filtration and ozonation at a municipal sewage treatment plant’, Water Res., 41, 4373-4382.

Oaks, J.L.; Gilbert, M.; Virani, M.Z.; Watson, R.T.; Meteyer, C.U.; Rideout, B.A.; Shivaprasad, H.L.; Ahmed, S.; Chaudhry, M.J.; Arshad, M.; Mahmood, S.; Ali, A.; Khan, A.A. (2004), ‘Diclofenac residues as the cause of vulture population decline in Pakistan’, Nature, 427(6975), 630-633.

Peng, X.; Wang, Z; Kuang, W; Tan, J.; Li, K. (2006), ‘A preliminary study on the occurrence and behavior of sulfonamides, ofloxacin and chloramphenicol antimicrobials in wastewaters of two sewage treatment plants in Guangzhou, China’, Sci. Total Environ., 371, 314-322.

Radjenović, J.; Petrović, M.; Barceló, D. (2009), ‘Fate and distribution of pharmaceuticals in wastewater and sewage sludge of the conventional activated sludge (CAS) and advanced membrane bioreactor (MBR) treatment’, Water Res., 43, 831-841.

Roberts, P. H.; Thomas, K .V. (2006), ‘The occurrence of selected pharmaceuticals in wastewater effluent and surface waters of the lower Tyne catchment’, Sci. Total Environ., 356, 143-153.

Sabourin, L.; Andrew Beck, A.; Duenk, P. W.; Kleywegt, S.; Lapen, D. R.; Li, H.; Metcalfe, C. D.; Payne, M.; Topp, E. (2009), ‘Runoff of pharmaceuticals and personal care products following application of dewatered municipal biosolids to an agricultural field‘, Sci. Total Environ., 407, 4596-4604

Santos, J. L.; Aparicio, I; Alonso, E.; Callejón, M. (2005),‘Simultaneous determination of pharmaceutically active compounds in wastewater samples by solid phase extraction and high performance liquid chromatography with diode array and fluorescence detectors’, Anal. Chim. Acta, 550, 116-122.

Scheurer, M.; Sacher, F.; Brauch, H-J. (2009), ‘Occurrence of the antidiabetic drug metformin in sewage and surface waters in Germany’, J. Environ. Monitor., 11, 1608-1613.

Smith, S. R. (2009), ‘Organic contaminants in sewage sludge (biosolids) and their significance for agricultural recycling’, Philos. T. Roy. Soc. A , 367, 4005-4011.

Spongberg, A. L.; Witter, J. D. (2008), ‘Pharmaceutical compounds in the wastewater process stream in Northwest Ohio’, Sci. Total Environ., 397, 148-157.

Stülten, D; Zühlke, S; Lamshöft, M.; Spiteller, M. (2008), ‘Occurrence of diclofenac and selected metabolites in sewage effluents’, Sci. Total Environ., 405, 310-316.

Terzić, S.; Senta, I.; Ahel, M.; Gros, M.; Petrović, M; Barcelo, D.; Müller, J.; Knepper, T.; Martí, I.; Ventura, F.; Jovančić, P., Jabučar, D. (2008), ‘ Occurrence and fate of emerging wastewater contaminants in Western Balkan Region’, Sci. Total Environ., 399, 66-77.

Topp, E.; Monteiro, S. C.; Beck, A.; Coelho, B. B.; Boxall, A. B .A.; Duenk, P. W.; Kleywegt, S.; Lapen, D. R.; Payne, M.; Sabourin, L.; Li, H.; Metcalfe, C. D. (2008), ‘Runoff of pharmaceuticals and personal care products following application of biosolids to an agricultural field’, Sci. Total Environ., 396, 52-59.

Touraud, E. (2008), ‘D6.6 KNAPPE final report’, available online http://www.knappe-eu.org/fichiers/60-D6.6%20final%20report%20final.pdf. Accessed 1/12/09.

Vieno, N.; Tuhkanen, T.; Kronberg, L. (2007), ‘Elimination of pharmaceuticals in sewage treatment plants in Finland’, Water Res., 41, 1001-1012.

Winkler, M.; Faika, D.; Gulyas, H.; Otterpohl R. (2008) ‘A comparison of human pharmaceutical concentrations in raw municipal wastewater and yellow water’, Sci. Total Environ., 399, 96-104.

Xu, W. ; Zhang, G.; Li X., Zou, S.; Li, P.; Hu, Z.; Li, J. (2007), ‘Occurrence and elimination of antibiotics at four sewage treatment plants in the Pearl River Delta (PRD), South China’, Water Res., 41, 4526-4534.

Ying, G-G.; Kookana, R. S.; Kolpin, D. W. (2009), ‘Occurrence and removal of pharmaceutically active compounds in sewage treatment plants with different technologies’, J. Environ. Monitor., 11, 1498-1505.

Yuan, F.; Hu, C.; Hu, X.; Qu, J.; Yang, M.; (2009), ‘Degradation of selected pharmaceuticals in aqueous solution with UV and UV/H2O2’, Water Res., 43, 1766-1774.

Zhang, Y.; Geißen, S.-U.; Gal C. (2008), ‘Carbamazepine and diclofenac: Removal in wastewater treatment plants and occurrence in water bodies’, Chemosphere, 73, 1151-1161.

Zhou, J. H. ; Zhang, Z L. ; Banks, E. ; Grover, D. ; Jiang, J. Q. (2009), ‘Pharmaceutical residues in wastewater treatment works effluents and their impact on receiving water’ , J. Hazard. Mater., 166, 655-661.

Zorita, S.; Mårtensson, L.; Mathiasson, L.(2009), ‘Occurrence and removal of pharmaceuticals in a municipal sewage treatment system in the south of Sweden’, Sci. Total Environ., 407, 2760-2770.