- Home

- About

- Environmental Briefs

-

Distinguished Guest Lectures

- 2023 Water, water, everywhere – is it still safe to drink? The pollution impact on water quality

- 2022 Disposable Attitude: Electronics in the Environment >

- 2019 Radioactive Waste Disposal >

- 2018 Biopollution: Antimicrobial resistance in the environment >

- 2017 Inside the Engine >

- 2016 Geoengineering >

- 2015 Nanomaterials >

- 2014 Plastic debris in the ocean >

- 2013 Rare earths and other scarce metals >

- 2012 Energy, waste and resources >

- 2011 The Nitrogen Cycle – in a fix?

- 2010 Technology and the use of coal

- 2009 The future of water >

- 2008 The Science of Carbon Trading >

- 2007 Environmental chemistry in the Polar Regions >

- 2006 The impact of climate change on air quality >

- 2005 DGL Metals in the environment: estimation, health impacts and toxicology

- 2004 Environmental Chemistry from Space

- Articles, reviews & updates

- Meetings

- Resources

- Index

Economic perspectives on water access and affordability

John W. Sawkins

School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London and King’s College London

Burlington House

ECB Bulletin July 2009

School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London and King’s College London

Burlington House

ECB Bulletin July 2009

Introduction

The supply of potable water to the urban population has long been recognised by public policymakers as one of the key underpinnings of civic society[1]. The public policy rationale underlying this has, however, proved rather difficult to pin down; with policymakers, ancient and modern, struggling to articulate clearly their particular policy objectives. Where clarity over objectives and the trade offs between them has been lacking, frequent recourse has been made to vague ‘water is special’ arguments for ex post justification of actions taken: an approach derided by Hirshleifer et al. (1960) as a smoke screen for sloppy thinking,

“Much nonsense has been written on the unique importance of water supply to the nation or to particular regions. Granted that the nation, or any individual thereof, could not survive without water, that does not show uniqueness. No human can survive without food, without oxygen…without clothing, yet somehow we do not have frequent conferences and symposiums of public-spirited bodies on “the clothing problem”…Whatever reason we cite, however, the alleged unique importance of water disappears upon analysis.” Hirshleifer, De Haven and Milliman (1960, pp 4-5)

For the purpose of this analysis, three policy objectives are suggested; echoing the three ‘pillars of sustainable development’ articulated at the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development[2]:

Clearly policymakers will consider all three objectives across time. However, this paper argues that at particular points in time the relative weight given to the different categories of objective will not only differ, but will be discernable from the statements and actions of policymakers themselves. In other words, one might work back from policy decisions and actions to policy priorities in a fairly straightforward way.

Changing public policy priorities

Evidence for a change in public policy priorities (in relation to the water industry in England and Wales) is offered by Bakker (2001). She suggests that over the past three decades the evolution of water charging policies has revealed a shift in public policy priorities, away from those emphasising social equity to those emphasising economic equity. Thus a system supporting the equalization of charges between regions via direct transfers between water authorities and companies was withdrawn, full cost recovery embraced and a system of economic regulation introduced to control the operations of the privatised regional water authorities. Some movement in the other direction has recently been observed with, for example, the ban on domestic disconnection for non-payment of charges. Nevertheless these and other recent changes have done little to alter the overall direction of travel.

In Scotland, a similar shift in public policy priorities may be discerned, albeit that this shift has been less pronounced and has occurred with a time lag. Thus more recently than in England and Wales, the principle of full cost recovery has been embraced, the complex system of water and sewerage charge reliefs for charitable and other organisations has been phased out, and an independent economic regulator[3] created to ensure the supplier works within strict economic and financial targets.

And so to this paper’s central question: what impact have these recent changes in public policy priorities had on low income households[4]?

Impact on low income households

In order to answer this we consider water ‘affordability’ which, in the UK, is understood as, and hence calibrated in terms of, the percentage of gross or net household income spent on water and sewerage services as a proportion of all income[5]. Thus the higher the proportion of household income spent on water and sewerage charges the less affordable those charges are deemed to be. The fact that domestic households may no longer suffer the ultimate sanction of disconnection for non-payment of charges underlies a preference in the literature for use of the term ‘water affordability’ rather than the more emotive and less genuinely descriptive ‘water poverty’. And whilst mitigating, it does not remove, the problem of economic access. Households who spend a high proportion of their income on water and sewerage services have fewer budgetary options than the wealthy. Those on an unmeasured supply arguably have even fewer options than those who pay by meter. Regardless of charging and payment method, however, where household incomes are inadequate to meet charges, debt levels rise bringing with it a number of well documented social problems[6].

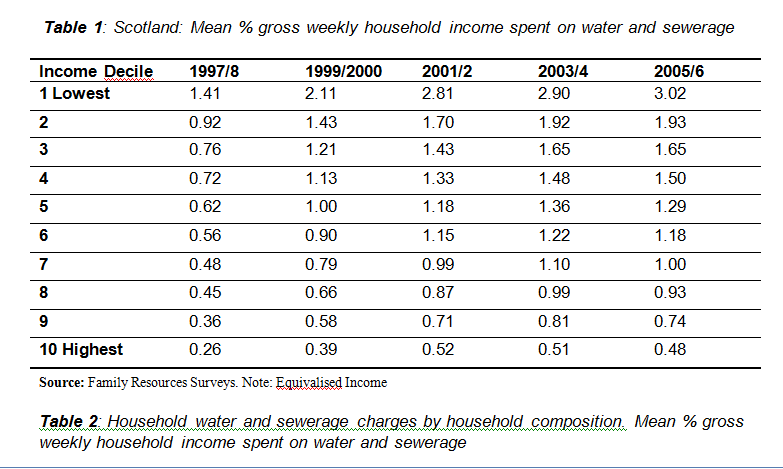

Drawing illustrative material from recent work relating to Scotland, Table 1 records the mean percentage gross weekly household income[7] spent on water and sewerage charges for households classified according to income deciles, at points in time between 1997/8 and 2005/6

The supply of potable water to the urban population has long been recognised by public policymakers as one of the key underpinnings of civic society[1]. The public policy rationale underlying this has, however, proved rather difficult to pin down; with policymakers, ancient and modern, struggling to articulate clearly their particular policy objectives. Where clarity over objectives and the trade offs between them has been lacking, frequent recourse has been made to vague ‘water is special’ arguments for ex post justification of actions taken: an approach derided by Hirshleifer et al. (1960) as a smoke screen for sloppy thinking,

“Much nonsense has been written on the unique importance of water supply to the nation or to particular regions. Granted that the nation, or any individual thereof, could not survive without water, that does not show uniqueness. No human can survive without food, without oxygen…without clothing, yet somehow we do not have frequent conferences and symposiums of public-spirited bodies on “the clothing problem”…Whatever reason we cite, however, the alleged unique importance of water disappears upon analysis.” Hirshleifer, De Haven and Milliman (1960, pp 4-5)

For the purpose of this analysis, three policy objectives are suggested; echoing the three ‘pillars of sustainable development’ articulated at the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development[2]:

- Social policy objectives which might include matters such as the promotion of public health and social inclusion.

- Economic policy objectives which might typically cover the management of public finances and the promotion of productive efficiency.

- Environmental policy objectives including species conservation and environmental protection.

Clearly policymakers will consider all three objectives across time. However, this paper argues that at particular points in time the relative weight given to the different categories of objective will not only differ, but will be discernable from the statements and actions of policymakers themselves. In other words, one might work back from policy decisions and actions to policy priorities in a fairly straightforward way.

Changing public policy priorities

Evidence for a change in public policy priorities (in relation to the water industry in England and Wales) is offered by Bakker (2001). She suggests that over the past three decades the evolution of water charging policies has revealed a shift in public policy priorities, away from those emphasising social equity to those emphasising economic equity. Thus a system supporting the equalization of charges between regions via direct transfers between water authorities and companies was withdrawn, full cost recovery embraced and a system of economic regulation introduced to control the operations of the privatised regional water authorities. Some movement in the other direction has recently been observed with, for example, the ban on domestic disconnection for non-payment of charges. Nevertheless these and other recent changes have done little to alter the overall direction of travel.

In Scotland, a similar shift in public policy priorities may be discerned, albeit that this shift has been less pronounced and has occurred with a time lag. Thus more recently than in England and Wales, the principle of full cost recovery has been embraced, the complex system of water and sewerage charge reliefs for charitable and other organisations has been phased out, and an independent economic regulator[3] created to ensure the supplier works within strict economic and financial targets.

And so to this paper’s central question: what impact have these recent changes in public policy priorities had on low income households[4]?

Impact on low income households

In order to answer this we consider water ‘affordability’ which, in the UK, is understood as, and hence calibrated in terms of, the percentage of gross or net household income spent on water and sewerage services as a proportion of all income[5]. Thus the higher the proportion of household income spent on water and sewerage charges the less affordable those charges are deemed to be. The fact that domestic households may no longer suffer the ultimate sanction of disconnection for non-payment of charges underlies a preference in the literature for use of the term ‘water affordability’ rather than the more emotive and less genuinely descriptive ‘water poverty’. And whilst mitigating, it does not remove, the problem of economic access. Households who spend a high proportion of their income on water and sewerage services have fewer budgetary options than the wealthy. Those on an unmeasured supply arguably have even fewer options than those who pay by meter. Regardless of charging and payment method, however, where household incomes are inadequate to meet charges, debt levels rise bringing with it a number of well documented social problems[6].

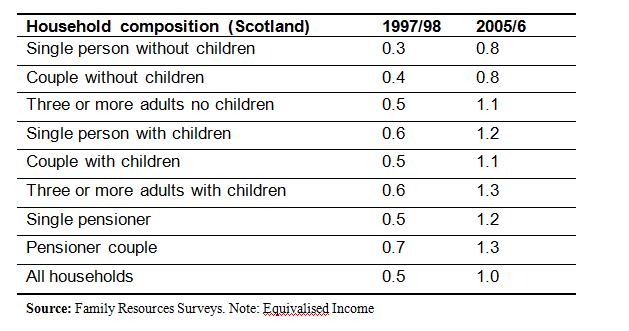

Drawing illustrative material from recent work relating to Scotland, Table 1 records the mean percentage gross weekly household income[7] spent on water and sewerage charges for households classified according to income deciles, at points in time between 1997/8 and 2005/6

|

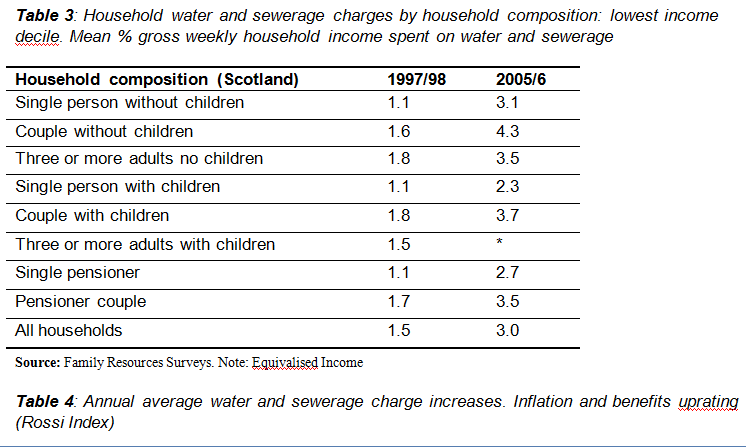

The change is marked and reflects, primarily, rapidly rising water and sewerage charges over the period following restructuring of the industry in 1996. Table 2 analyses the same period by household composition, whilst Table 3 focuses only on households in the lowest income decile. A similar pattern of increased proportions of household income spent on these services is observed.

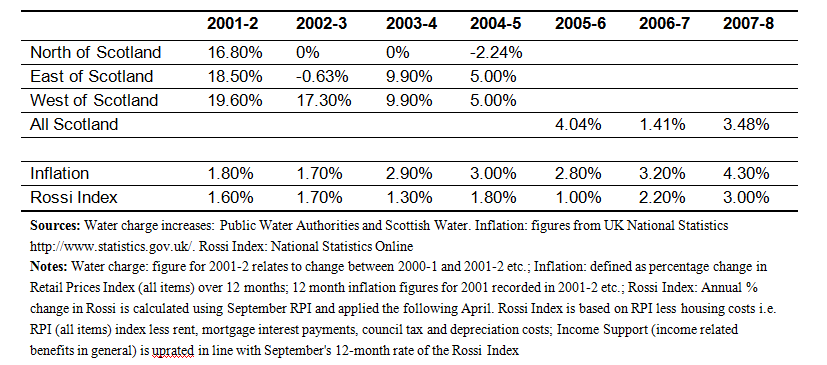

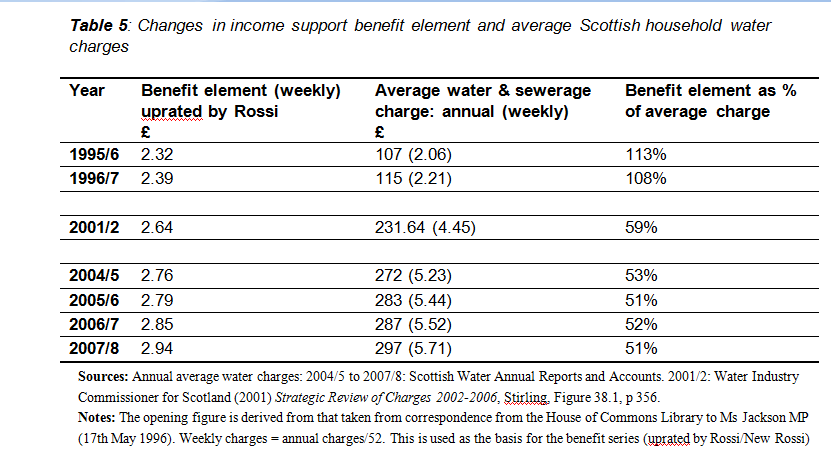

Changes in charge levels are, of course, only one aspect of affordability. Another is the changes in income levels which, for households in the lowest income decile, are bound up with changes in social security benefit arrangements. Without describing current social security arrangements in detail it is sufficient to note that there is currently no dedicated benefit relating to water and sewerage charges. Simplifying somewhat, the primary benefit that may be applied by households to their water charges is the personal allowance element of income support, a means tested benefit which is increased annually according to an index – the Rossi index – applied by the Government. Whilst indexation of benefits does seek to mitigate the effect of inflation on the purchasing power of households it does not, indeed cannot, do that perfectly. More problematic from the point of view of water affordability however is the extent to which this indexation has lagged behind increases in water and sewerage charges. Table 4 sets this out clearly by recording annual average water and sewerage charge increases alongside a measure of inflation[8] and the Rossi index used for benefits uprating. To analyse the extent to which benefits indexation has lagged water and sewerage charge increases in Scotland over the last decade, Table 5 records the notional benefit element within the income support personal allowance attributable to water as a percentage of the average charge. As is clear from the Table from the claimant’s point of view the position has deteriorated markedly during this period. Affordability and increasing water scarcity So much for the recent past: what of the near future? Clearly social and economic concerns will continue to influence the evolution of public policy towards water. More significantly, however, we might anticipate that greater priority will be given to environmental objectives as the Government seeks to implement the European Union’s Water Framework Directive against a backdrop of increasing water scarcity. Already political debate over new charging structures to support environmental objectives such as species preservation and environmental protection is well advanced in the UK. As this debate matures it will be important not only to track its development, but to undertake research into the impact of environmentally inspired initiatives on low income and economically vulnerable households. Without this, the chance of building a lasting public policy consensus over water and sewerage service delivery over the next decade – one of the key underpinnings of civic society – seems remote. |

|

References

Bakker, K. J. (2001), ‘Paying for water: water pricing and equity in England and Wales’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, NS 26, 143-164.

Family Resources Survey, 1997-98 [computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], 10 January 2000. SN: 4068.

Family Resources Survey,1999-2000 [computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], 12 September 2001. SN: 4389.

Family Resources Survey, 2001-2002 [computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], 8 May 2003. SN: 4633.

Family Resources Survey, 2003-2004 [computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], 6 April 2005. SN: 5139.

Family Resources Survey, 2005-2006 [computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], 16 November 2007. SN: 5742.

Hirshleifer, J. De Haven, J.,C. and Milliman, J.,W. (1960), Water Supply: Economics, Technology and Policy, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London.

Save the Children (1996), Water Tight: The Impact of Water Metering on Low-income Families, Save the Children, London.

Sawkins, J. W.; Dickie, V. A. 2005, ‘Affordability of household water and sewerage services in Great Britain’, Fiscal Studies, 26, No. 2, 225-244.

Scottish Water (various), Annual Report and Accounts, Scottish Water, Dunfermline, Scotland.

Professor JOHN W. SAWKINS,

Department of Economics,

School of Management and Languages,

Heriot Watt University

Edinburgh EH14 4AS

Bakker, K. J. (2001), ‘Paying for water: water pricing and equity in England and Wales’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, NS 26, 143-164.

Family Resources Survey, 1997-98 [computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], 10 January 2000. SN: 4068.

Family Resources Survey,1999-2000 [computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], 12 September 2001. SN: 4389.

Family Resources Survey, 2001-2002 [computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], 8 May 2003. SN: 4633.

Family Resources Survey, 2003-2004 [computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], 6 April 2005. SN: 5139.

Family Resources Survey, 2005-2006 [computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], 16 November 2007. SN: 5742.

Hirshleifer, J. De Haven, J.,C. and Milliman, J.,W. (1960), Water Supply: Economics, Technology and Policy, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London.

Save the Children (1996), Water Tight: The Impact of Water Metering on Low-income Families, Save the Children, London.

Sawkins, J. W.; Dickie, V. A. 2005, ‘Affordability of household water and sewerage services in Great Britain’, Fiscal Studies, 26, No. 2, 225-244.

Scottish Water (various), Annual Report and Accounts, Scottish Water, Dunfermline, Scotland.

Professor JOHN W. SAWKINS,

Department of Economics,

School of Management and Languages,

Heriot Watt University

Edinburgh EH14 4AS