- Home

- About

- Environmental Briefs

-

Distinguished Guest Lectures

- 2023 Water, water, everywhere – is it still safe to drink? The pollution impact on water quality

- 2022 Disposable Attitude: Electronics in the Environment >

- 2019 Radioactive Waste Disposal >

- 2018 Biopollution: Antimicrobial resistance in the environment >

- 2017 Inside the Engine >

- 2016 Geoengineering >

- 2015 Nanomaterials >

- 2014 Plastic debris in the ocean >

- 2013 Rare earths and other scarce metals >

- 2012 Energy, waste and resources >

- 2011 The Nitrogen Cycle – in a fix?

- 2010 Technology and the use of coal

- 2009 The future of water >

- 2008 The Science of Carbon Trading >

- 2007 Environmental chemistry in the Polar Regions >

- 2006 The impact of climate change on air quality >

- 2005 DGL Metals in the environment: estimation, health impacts and toxicology

- 2004 Environmental Chemistry from Space

- Articles, reviews & updates

- Meetings

- Resources

- Index

Inside the engine: From chemistry to human health

The 2017 ECG Distinguished Guest Lecture and symposium was held on 1st March 2017, exploring the chemistry of diesel engine emissions, emissions policy, and how this is affecting human health. The ECG Distinguished Guest Lecture was given by Professor Frank Kelly, King’s College London.

In the introductory talk, Dr Claire Holman (University College London/Brook Cottage Consultants) explored the links between diesel vehicles and poor air quality. Today, media interest in this topic is higher than it has been at any time since the late 1980s/early 1990s. The key air pollutants in most of our cities are nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and fine particulate matter (PM) in urban areas, both of which are predominantly emitted by diesel engines. Indeed, most of the air quality management areas in the UK are due to high concentrations of NO2. The biggest contributor to NOx (oxides of nitrogen, including NO2) is road traffic (80%).

|

Vehicle manufacturers tend to prefer to improve vehicle emissions by improving the engine rather than adding an additional component to treat the exhaust. However, there is a trade-off between generating CO2, NOx and particulates; often if the engine is improved to treat one type of emission then issues can arise with another type. For example, reducing CO2 and hydrocarbon emissions can lead to an increase NOx emissions. CO2 is the primary cause of climate change, which is a global issue requiring global agreement whereas air pollution is a more regional or national issue, where local and national action can have direct benefits for local inhabitants. This disconnect results in an interesting tension between efforts to tackle climate change and air pollution.

|

Vehicle emissions are measured in a laboratory using a chassis dynamometer to confirm compliance with the EU Type Approval test. Emission test results show that emissions from diesel cars have improved substantially in the last decade, but are still considerably higher than those for petrol cars. Yet, currently around 30% of cars (and 50% of new cars) are diesel, largely because of incentives for buying them as they were perceived to be better for the climate (lower CO2 emissions per kilometre travelled). Critically, the reduction in emissions observed in the laboratory tests have not been reflected in data from real driving conditions, which are typically up to six times greater.

All new cars have some sort of abatement technology fitted, but to aid performance these are not always activated under all driving conditions. In fact, many car manufacturers installed ‘defeat devices’, which switch off pollution control technology after a certain period of time or below a threshold temperature to avoid engine damage. For example, the vehicles produced by one manufacturer switches off their pollution control after 22 minutes (and it has been noted that the typical laboratory emission test lasts 20 minutes), and others may be predominantly switched off in temperatures typical of northern European climates.

Although Volkswagen received much of the bad press, Dr Holman concluded that their most recent models actually had one of the lowest on-road emissions, compared to other manufacturers, although their on-road real world emissions were still nearly double the test cycle limit for NOx. As a result of these issues, from 2019 all new vehicles will be subject to a ‘real driving’ emissions test with the permitted limit initially being 2.1 times that for the laboratory tests in 2019, and this will decrease to 1.5 times by 2020/21.

Although Volkswagen received much of the bad press, Dr Holman concluded that their most recent models actually had one of the lowest on-road emissions, compared to other manufacturers, although their on-road real world emissions were still nearly double the test cycle limit for NOx. As a result of these issues, from 2019 all new vehicles will be subject to a ‘real driving’ emissions test with the permitted limit initially being 2.1 times that for the laboratory tests in 2019, and this will decrease to 1.5 times by 2020/21.

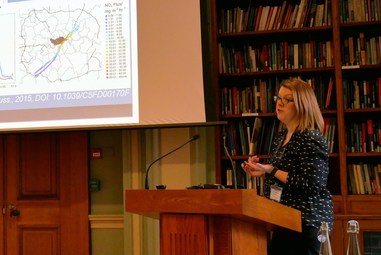

Dr Jacqueline Hamilton (University of York) began her talk by noting that diesel use is increasing worldwide, not just in Europe, and by 2040 diesel will be the predominant fuel globally. After exiting the engine in modern vehicles, diesel emissions in modern vehicles including NOx, CO, CO2, PM, volatile organic carbon compounds (VOCs) and unburnt fuel pass through an oxidising catalyst, then a diesel particulate filter, before being emitted as exhaust. VOCs are important as they can be oxidised to form ozone, are implicated in the oxidation of NO to NO2 and can form secondary organic aerosols (SOAs) through condensation onto pre-existing aerosols. Both ozone and SOAs are known to be toxic.

|

The concentrations of pollutants measured in the atmosphere by flying a plane over London were much larger than calculations based upon the National Emissions Inventory would suggest. There has been controversy over the role that diesel plays in generating SOA. Although levels of smaller hydrocarbons in the air are falling, the speaker argued that the (largely neglected) intermediate size (>C10) volatile organic compounds from diesel exhaust may be key to understanding the concentrations of SOAs in the atmosphere. This is becoming more important as diesel cars are now known to be the largest contributor to urban SOA formation when they make up more than 10% of cars on the road.

|

Measuring VOC emissions is difficult and has therefore often been overlooked. They are present at parts per billion to parts per trillion concentrations in a complex matrix (air), and have a vast range of polarities and isomeric complexity. A new technique called two dimensional mass spectrometry (GC-GC-MS) can separate out over 600 VOCs from an urban air sample. This is a powerful tool to identify the sources of hydrocarbons in the atmosphere and, potentially, their contribution to SOA formation. Two dimensional gas chromatography has been used to measure VOCs in London air and in diesel exhaust in laboratory test conditions, and the most recent deployment is in a project looking at air quality in Beijing.

|

While the National Emissions Inventory shows good agreement with atmospheric measurements for molecules with few carbon atoms, those greater than C10 in size can be underestimated by a factor of 70. However, this discrepancy can be accounted for once the emission of intermediate VOCs from diesel engines is included in the models. Dr Hamilton concluded that diesel emissions contribute up to 30% of SOA in the UK. The shift to diesel in the UK has changed the balance of hydrocarbons in the atmosphere, but this shift has been unnoticed due to a lack of measurement infrastructure. However, new research is now highlighting the importance of pollutants other than CO2 and NO2 from diesel emissions.

|

Simon Birkett (Clean Air London) explained that modern air quality legislation was first introduced by the Clean Air Act of 1956 following the Great London Smog in 1952. However, London currently has some of the highest NO2 concentrations in the world. Mr Birkett therefore asserted that similar pioneering action needs to be taken.

|

In the 1980s, concerns rose about lead in petrol, leading to the development of the three way catalytic converter. The Thatcher government played a key role in developing UK environmental policy, which was first published in the ‘This Common Inheritance’ report in 1990 and discussed unleaded petrol, carbon dioxide and ozone. Even in 1990/1991, there was knowledge and awareness of the health effects of diesel emitted particles (the 1992 issue mentioned that small particles from diesel fuel may contribute to cancer). But it was not until 2012 that the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified diesel fuel as carcinogenic. During the early 1990s, a focus on fuel efficiency and hence lower CO2 emissions meant that diesel was nevertheless prioritised. Since then, all successive governments have promoted diesel to act on climate change concerns.

|

Mr Birkett compared effect of diesel emissions on air quality today to passive smoking in the 1970s; health impacts were acknowledged by the WHO, but efforts to tackle the problem still took decades. Moreover, he called it ironic that increasing diesel use has not lowered carbon dioxide emissions, as originally intended. The speaker called for a “One Atmosphere” strategy that does not focus just on air quality or on carbon dioxide, but rather tackles both at the same time. His ambition would be to rid London of all fossil fuels by 2033 — this would require acting now as, for example, new diesel taxis registered this year will be around for 15 years.

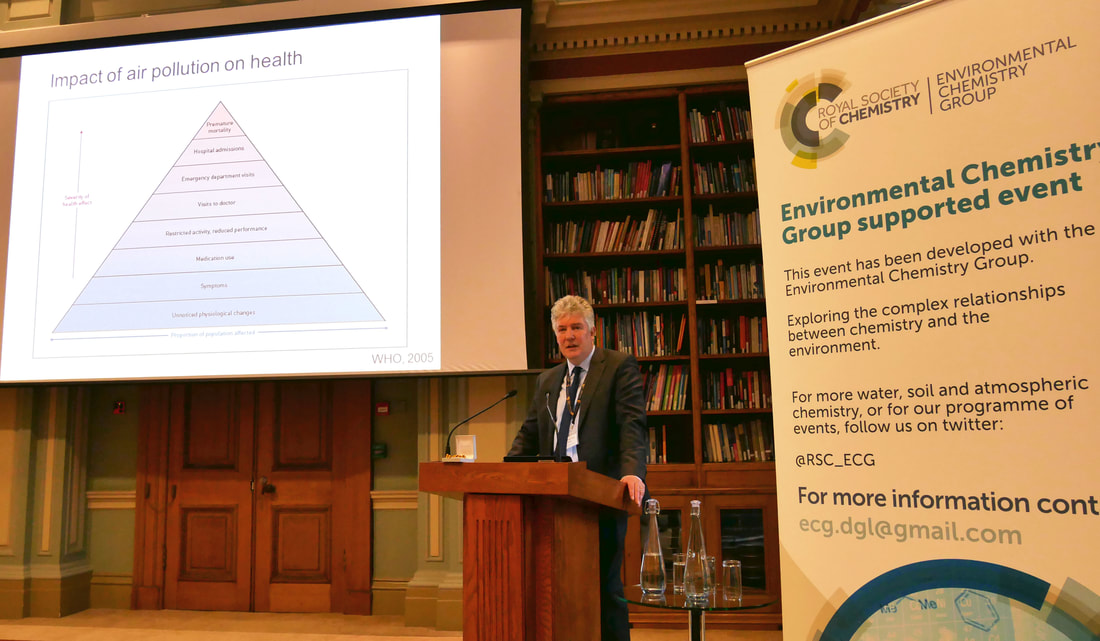

The symposium closed with the ECG Distinguished Guest Lecturer, Professor Frank Kelly (King’s College London), who spoke on “Traffic Pollution and Health in London, Umea and Beijing”. He began his talk by describing the WHO air pollution pyramid; at the bottom all people exposed to air pollution have unnoticed (but consequential) physiological changes. Moving up, a proportion of people will have symptoms such as running eyes and asthma, and at the top of the pyramid there are 29,000 annual deaths in the UK linked to particles in the atmosphere (PM2.5).

Umea in Sweden has pristine air and world class research facilities and is thus a perfect place to study the effects of air pollution using an ozone exposure chamber or by performing investigative bronchoscopy on medical student volunteers after controlled exposure to air pollution. A two-hour exposure to ozone caused an inflammatory response, with neutrophils shown to enter the lungs. This effect was also observed after exposure to diesel exhaust at concentrations commonly found in the environment, as well as the expression of genes associated with an immune system response, and activation of bronchial mucosal cells.

Umea in Sweden has pristine air and world class research facilities and is thus a perfect place to study the effects of air pollution using an ozone exposure chamber or by performing investigative bronchoscopy on medical student volunteers after controlled exposure to air pollution. A two-hour exposure to ozone caused an inflammatory response, with neutrophils shown to enter the lungs. This effect was also observed after exposure to diesel exhaust at concentrations commonly found in the environment, as well as the expression of genes associated with an immune system response, and activation of bronchial mucosal cells.

|

The immune response to particulates in our lungs damages the tissues and causes long term impacts. Macrophages engulf black carbon particles (from diesel exhaust) in the lungs, and try to destroy them as they would a bacterial invader by producing free radicals. As there is no bacterium to absorb the free radicals, they end up killing the macrophages and causing small levels of cellular damage. Moreover, particles contain metals and organic compounds, so also cause complex chemical reactions at the lung surface. Damage accumulates over time and can lead to disease such as chronic exposure disease, but the response to air pollution varies widely between subjects. This variation is typical of human exposure studies, and an important aspect of this research is to understand which factors affect this variation and why.

|

Professor Kelly described experiments that he and his coworkers had conducted using Oxford Street and Hyde Park in London as a natural laboratory to study exposure to ‘high’ and ‘low’ pollution levels. The first experiment involved asking asthmatics to take a two hour walk before measuring their lung function using spirometry. Not only was lung function reduced after exposure to Oxford Street pollution (and compared to those who walked in Hyde Park), it was also still reduced 22 hours later. Researchers in Germany found that you have a higher risk of coronary artery calcification (which can lead to heart attacks) the closer you live to a main road, so Professor Kelly used the Oxford Street and Hyde Park natural laboratory to see what effect air pollution had on people with lung disease. Results showed increased airway resistance in ischaemic heart disease patients and increased airway dysfunction and arterial stiffness in patients suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

A six year study called EXHALE of children at schools close to main roads, conducted in East London, investigated how exposure to NOx, NO2, PM10 and PM2.5 might impact on their lung development. The results showed that everyday exposure to air pollution had an adverse effect on lung growth in children. Those exposed to 35 μg/m3 NO2 had lost 105 ml of lung capacity (5.5%); those with higher exposures of 55 μg/m3 had lost 165 ml (8.7%). If this deficit is not remedied before the children stop growing, they will have reduced lung capacity throughout their lives. The researchers also found evidence for black carbon from diesel in the children’s lungs. Around 65% of their exposure was from their journey to school or in the playground.

In the final part of his lecture, Professor Kelly shifted attention to his recent work in China. The problems seen in London pale into insignificance compared to those in many parts of East Asia today, where heavy traffic and industrial emissions cause severe smog in cities, while indoor air pollution from cooking stoves dominates in rural areas. Ambient air pollution is the fourth biggest killer in China and indoor air pollution is the fifth. Most vehicles in China run on petrol. In ongoing work in Beijing, the researchers have recruited two groups of 120 subjects at two sites, one in the city and one in a nearby rural location. They are using sophisticated personal monitors to gain a detailed picture of individual exposure to a range of pollutants, compare the effects of outdoor and indoor air pollution, and identify the resulting health impacts, with physiological and gene expression studies.

| programme__into_the_engine.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1002 kb |

| File Type: | |

Banner image: Rush hour traffic on a city road. Credit: Repina Valeriya/Shutterstock