- Home

- About

- Environmental Briefs

-

Distinguished Guest Lectures

- 2023 Water, water, everywhere – is it still safe to drink? The pollution impact on water quality

- 2022 Disposable Attitude: Electronics in the Environment >

- 2019 Radioactive Waste Disposal >

- 2018 Biopollution: Antimicrobial resistance in the environment >

- 2017 Inside the Engine >

- 2016 Geoengineering >

- 2015 Nanomaterials >

- 2014 Plastic debris in the ocean >

- 2013 Rare earths and other scarce metals >

- 2012 Energy, waste and resources >

- 2011 The Nitrogen Cycle – in a fix?

- 2010 Technology and the use of coal

- 2009 The future of water >

- 2008 The Science of Carbon Trading >

- 2007 Environmental chemistry in the Polar Regions >

- 2006 The impact of climate change on air quality >

- 2005 DGL Metals in the environment: estimation, health impacts and toxicology

- 2004 Environmental Chemistry from Space

- Articles, reviews & updates

- Meetings

- Resources

- Index

An introduction to the global crisis of antimicrobial resistance

Andrew C Singer

NERC Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Wallingford

[email protected]

ECG Bulletin July 2018

NERC Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Wallingford

[email protected]

ECG Bulletin July 2018

Antimicrobials are chemicals that are used to kill or inhibit the growth of microorganisms. Their use in medicine has spanned over 80 years, during which time their overuse and misuse in humans and animals, and their reckless release into the environment, has nurtured a global crisis of drug-resistant pathogens.

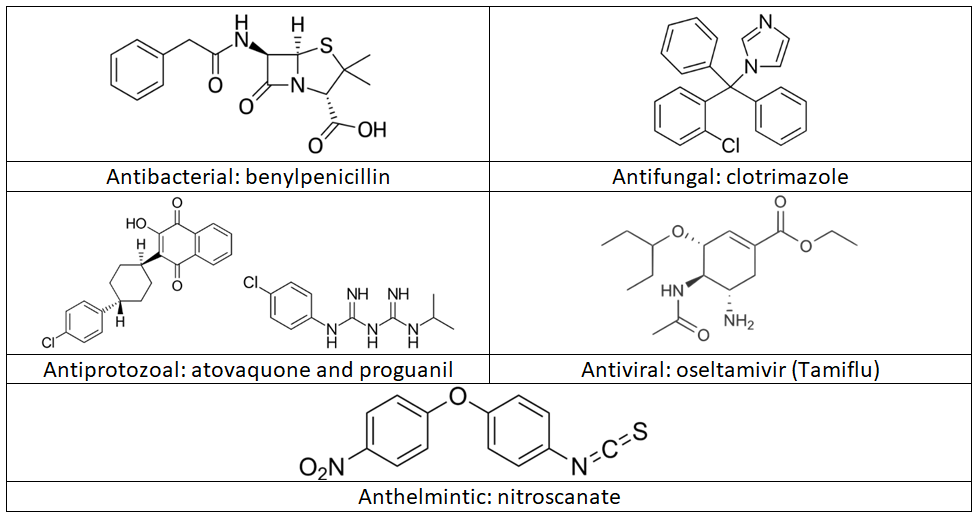

The term ‘antimicrobials’ includes a wide range of chemicals antagonistic towards five categories of organisms: 1) antivirals, inhibitors of viral replication; 2) antibacterials, which kill or inhibit the replication of bacteria; 3) antifungals, which kill or inhibit fungi; 4) antiprotozoals, which kill or inhibit the replication of protists; and 5) anthelmintics, which kill or inhibit worms. A typical example of an antimicrobial in each category is shown in Figure 1. The global movement to combat antimicrobial resistance (AMR) includes efforts to tackle infections resistant to drugs from each of these five categories. However, the main focus of most AMR Action Plans is on antibacterials.

The term ‘antimicrobials’ includes a wide range of chemicals antagonistic towards five categories of organisms: 1) antivirals, inhibitors of viral replication; 2) antibacterials, which kill or inhibit the replication of bacteria; 3) antifungals, which kill or inhibit fungi; 4) antiprotozoals, which kill or inhibit the replication of protists; and 5) anthelmintics, which kill or inhibit worms. A typical example of an antimicrobial in each category is shown in Figure 1. The global movement to combat antimicrobial resistance (AMR) includes efforts to tackle infections resistant to drugs from each of these five categories. However, the main focus of most AMR Action Plans is on antibacterials.

Alexander Fleming’s characterisation of the antibacterial properties of the culture broth of Penicillium chrysogenum was the catalyst for modern antibacterials (1) . However, it is less widely known that the motivation behind this original finding was to improve the culture conditions for Bacillus influenzae growth in the laboratory (now known as Haemophilus influnezae). At the time of Fleming’s research in the late 1920s, B. influenzae was presumed to be the infective agent behind the Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918 — a pandemic responsible for infecting 500 million people worldwide, and killing between 5 to 10% of those infected (2). Fleming felt that the antibacterial properties of the P. chrysogenum would be useful in producing pure cultures of the bacterial pathogen, thereby aiding the drive towards the discovery of a vaccine against this bacterium. The first evidence of the viral origin of influenza was published around the time of Fleming’s Nobel Prize-winning paper, in 1929.

Fleming never fully characterised nor isolated the active ingredient in the fungal broth; this was completed by a team led by Ernst Chain and Howard Florey (3). Chain and Florey shared the Nobel Prize in Medicine with Fleming in 1945, the same year that a pioneering x-ray crystallographer in the Florey team, Dorothy Hodgkin, proposed the first 3D structure of penicillin. Hodgkin’s achievement earned her membership in the Royal Society in 1947. In 1964, she won the Nobel Prize for her ‘X-ray Analysis of Complicated Molecules’ including benzylpenicillin, cephalosporin and vitamin B12 (4).

In the years following the research from the Florey group, hundreds of antibiotics were discovered from bacteria and fungi, or developed as a modified form of existing antibiotics (5). Concurrent with each newly marketed antibiotic was the observation of resistant microorganisms. Until recently, it was commonly believed that the emergence of an antibiotic resistance gene was the direct result of natural selection in vivo. Although many clinicians still hold on to this belief, it is now clear that most of the resistance mechanisms currently relied upon by microorganisms have been in the resistome (the pool of all resistance genes in a habitat) for thousands or perhaps millions of years. This means that nearly every antibiotic resistance gene first evolved in a microbe found in the environment. The rare but inevitable event of human pathogens acquiring this gene was facilitated by much of humanity’s poor hygiene practices, including the lack of sanitation and the ubiquitous release of pollutants into our environment (6, 7).

In the years following the research from the Florey group, hundreds of antibiotics were discovered from bacteria and fungi, or developed as a modified form of existing antibiotics (5). Concurrent with each newly marketed antibiotic was the observation of resistant microorganisms. Until recently, it was commonly believed that the emergence of an antibiotic resistance gene was the direct result of natural selection in vivo. Although many clinicians still hold on to this belief, it is now clear that most of the resistance mechanisms currently relied upon by microorganisms have been in the resistome (the pool of all resistance genes in a habitat) for thousands or perhaps millions of years. This means that nearly every antibiotic resistance gene first evolved in a microbe found in the environment. The rare but inevitable event of human pathogens acquiring this gene was facilitated by much of humanity’s poor hygiene practices, including the lack of sanitation and the ubiquitous release of pollutants into our environment (6, 7).

|

It is a fundamental law of nature that any chemical that results in the reduction in growth or the killing of a microbe will ultimately drive natural selection towards ‘solutions.’ A conservative estimate suggests that 13% of all biomass on earth are microbes (8). Their short generation time, relative to macroorganisms, helps ensure their adaptation to any chemical challenge. Microbial adaptation to chemical antagonism applies not only to antibiotics, but also to ‘natural’ pollutants such as metals (e.g. Zn, Cd, Ni, Cu) and plant secondary metabolites (9, 10).

All microorganisms harbour resistance genes, without which they would have no ‘immune system’. Some of the resistance genes are clinically important, while most afford a basic level of protection. The problem arises when clinically-relevant resistance genes are shared. Microorganisms acquire resistance genes through a range of genetic mechanisms termed mobile genetic elements. Without mobile genetic elements, the challenge of tackling AMR would be considerably easier.

|

However, this feature not only allows for the sharing of solutions to chemical challenges among bacteria, but it also allows these solutions to be clustered together in tightly packed mobile genetic units called plasmids (11). Plasmids can be shared, allowing previously susceptible micro-organism to acquire resistance to the immediate chemical threat and, critically, simultaneously to acquire solutions to numerous other chemical threats found on the plasmid. It is a bit like seeking travel insurance to cover an unadventurous trip to the beach and being offered, at the same cost, worldwide travel insurance that covers ski trips, cancelled airlines and lost luggage. The term for this in the clinical setting is ‘multi-drug resistance’ (MDR).

MDR is maintained in environmental microbes through the release of pollutant mixtures. Once a chemical’s concentration is above the threshold that inhibits the growth of a microbe, this pollutant becomes ecologically important as it will be driving the selection of resistance genes. The lower the selection threshold, the more significant the effect of the pollutant, whereupon even trace amounts of these chemicals can select for resistance. Importantly, the resistance genes do not necessarily disappear once the threshold is no longer met. Resistance genes found on a plasmid, for example, will be retained as long as one of the genes found on the plasmid offers a selective advantage (12). So, if a plasmid with an antibiotic resistance gene is no longer in use, it can remain present in a population of microbes if they inhabit an environment where, for example, zinc is abundant, and the zinc resistance gene is co-located on the same plasmid as the aforementioned antibiotic resistance gene. To use a metaphor, you still have ski insurance even if you don’t go skiing, as it comes ‘free’ with the insurance package. Importantly, it is the problem of the co-selecting potential of pollution mixtures, not just antibiotics, that must be overcome to achieve significant gains in combatting global antimicrobial resistance.

The future utility of antibiotics will be reliant on our ability to address the contaminantion we release into the environment. The challenge of combating contaminants is a global one and it must coincide with improvements in hygiene and sanitation to be sustainable.

References

1. Fleming, A. (1929) On the Antibacterial Action of Cultures of a Penicillium, with Special Reference to their Use in the Isolation of B. influenzæ. Br. J. Exp. Pathol., 10, 226-236

2. Taubenberger, J.K. and Morens, D.M. (2008) The pathology of influenza virus infections. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 3: 499–522.

3. Chain, E., Florey, H.W., Gardner, A.D., Heatley, N.G., Jennings, M.A., Orr-Ewing, J., and Sanders, A.G. (1940) Penicillin as a Chemotherapeutic Agent. The Lancet 236: 226–228.

4. Hodgkin, D.C. (1965) The x-ray analysis of complicated molecules. Science. 150: 979–988.

5. Aminov, R.I. (2010) A brief history of the antibiotic era: lessons learned and challenges for the future. Front. Microbiol. 1: 134.

6. United Nations Environment Programme (2017) UNEA 3 Report: Towards a Pollution-Free Planet - Background Repor (c) United Nations Environment Programme, 2017, ISBN: 978-92-807-3669-4

7. Chief Medical Officer Annual Report 2017: Health impacts of all pollution – What do we know? (2018) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chief-medical-officer-annual-report-2017-health-impacts-of-all-pollution-what-do-we-know

8. Bar-On, Y.M., Phillips, R., and Milo, R. (2018) The biomass distribution on Earth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 201711842, published ahead of print May 21 2018.

9. Singer, A.C., Crowley, D.E., and Thompson, I.P. (2003) Secondary plant metabolites in phytoremediation and biotransformation. Trends Biotechnol. 21: 123–130.

10. Singer, A.C., Thompson, I.P., and Bailey, M.J. (2004) The tritrophic trinity: a source of pollutant-degrading enzymes and its implications for phytoremediation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7: 239–244.

11. Salto, I.P., Torres Tejerizo, G., Wibberg, D., Pühler, A., Schlüter, A., and Pistorio, M. (2018) Comparative genomic analysis of Acinetobacter spp. plasmids originating from clinical settings and environmental habitats. Sci. Rep. 8: 7783.

12. Lopatkin, A.J., Meredith, H.R., Srimani, J.K., Pfeiffer, C., Durrett, R., and You, L. (2017) Persistence and reversal of plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance. Nat Comm 8: 1689.

MDR is maintained in environmental microbes through the release of pollutant mixtures. Once a chemical’s concentration is above the threshold that inhibits the growth of a microbe, this pollutant becomes ecologically important as it will be driving the selection of resistance genes. The lower the selection threshold, the more significant the effect of the pollutant, whereupon even trace amounts of these chemicals can select for resistance. Importantly, the resistance genes do not necessarily disappear once the threshold is no longer met. Resistance genes found on a plasmid, for example, will be retained as long as one of the genes found on the plasmid offers a selective advantage (12). So, if a plasmid with an antibiotic resistance gene is no longer in use, it can remain present in a population of microbes if they inhabit an environment where, for example, zinc is abundant, and the zinc resistance gene is co-located on the same plasmid as the aforementioned antibiotic resistance gene. To use a metaphor, you still have ski insurance even if you don’t go skiing, as it comes ‘free’ with the insurance package. Importantly, it is the problem of the co-selecting potential of pollution mixtures, not just antibiotics, that must be overcome to achieve significant gains in combatting global antimicrobial resistance.

The future utility of antibiotics will be reliant on our ability to address the contaminantion we release into the environment. The challenge of combating contaminants is a global one and it must coincide with improvements in hygiene and sanitation to be sustainable.

References

1. Fleming, A. (1929) On the Antibacterial Action of Cultures of a Penicillium, with Special Reference to their Use in the Isolation of B. influenzæ. Br. J. Exp. Pathol., 10, 226-236

2. Taubenberger, J.K. and Morens, D.M. (2008) The pathology of influenza virus infections. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 3: 499–522.

3. Chain, E., Florey, H.W., Gardner, A.D., Heatley, N.G., Jennings, M.A., Orr-Ewing, J., and Sanders, A.G. (1940) Penicillin as a Chemotherapeutic Agent. The Lancet 236: 226–228.

4. Hodgkin, D.C. (1965) The x-ray analysis of complicated molecules. Science. 150: 979–988.

5. Aminov, R.I. (2010) A brief history of the antibiotic era: lessons learned and challenges for the future. Front. Microbiol. 1: 134.

6. United Nations Environment Programme (2017) UNEA 3 Report: Towards a Pollution-Free Planet - Background Repor (c) United Nations Environment Programme, 2017, ISBN: 978-92-807-3669-4

7. Chief Medical Officer Annual Report 2017: Health impacts of all pollution – What do we know? (2018) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chief-medical-officer-annual-report-2017-health-impacts-of-all-pollution-what-do-we-know

8. Bar-On, Y.M., Phillips, R., and Milo, R. (2018) The biomass distribution on Earth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 201711842, published ahead of print May 21 2018.

9. Singer, A.C., Crowley, D.E., and Thompson, I.P. (2003) Secondary plant metabolites in phytoremediation and biotransformation. Trends Biotechnol. 21: 123–130.

10. Singer, A.C., Thompson, I.P., and Bailey, M.J. (2004) The tritrophic trinity: a source of pollutant-degrading enzymes and its implications for phytoremediation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7: 239–244.

11. Salto, I.P., Torres Tejerizo, G., Wibberg, D., Pühler, A., Schlüter, A., and Pistorio, M. (2018) Comparative genomic analysis of Acinetobacter spp. plasmids originating from clinical settings and environmental habitats. Sci. Rep. 8: 7783.

12. Lopatkin, A.J., Meredith, H.R., Srimani, J.K., Pfeiffer, C., Durrett, R., and You, L. (2017) Persistence and reversal of plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance. Nat Comm 8: 1689.