Masters of disaster - click to change the world

This interactive, public event was hosted by Science Oxford and the ECG. It took place in Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, on Monday 21 November 2016 and was attended by thirty-two participants. The event diverged from other events by making use of interactive technology and by encouraging academic speakers to speculate about the future based on their expert knowledge. The audience was able to steer the direction of the debate and explore possible futures.

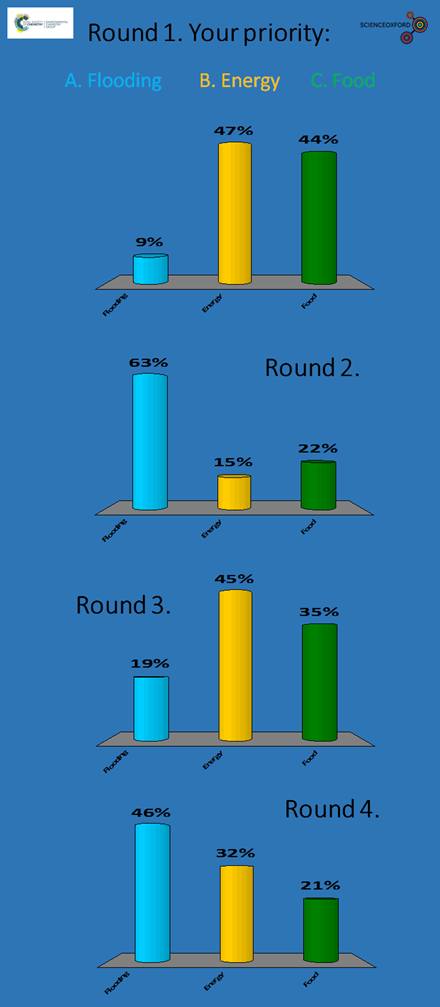

Imagine yourself a hundred years in the future. No further changes have been made to mitigate climate change and we are now in an energy crisis, places like Oxford are flooded continuously, and food scarcity is a global problem. What can we do to address and prioritise these issues? At the start of the event, each speaker gave a 5-10 minute talk or “pitch,” followed by an audience vote using Turning Point handsets – an interactive technology that allows live vote collection and data display in Powerpoint presentations. Following the revelation of the votes, the speakers responded, and the story of the future’s crisis unfolded.

Speaking at the event were Dr Caspar Hewett (Newcastle University), Professor Myles Allen (University of Oxford Environmental Change Institute), and Dr Marcus Springman (Oxford Martin School). The event was chaired by Dr Michaela Livingstone from Oxford Sparks, a public engagement platform for science at the University of Oxford.

Dr Caspar Hewett first put forward the case for both large- and small-scale flood interventions, from draining reservoirs before predicted heavy rainfall and digging holes to divert excess water and delay its entry into rivers, to planetary-scale geoengineering approaches. The two geoengineering methods that he supported were the use of “Salter’s ships” spraying seawater into the air to increase Earth’s albedo, thereby reflecting the sun’s rays back into space and cooling the planet, and CO2 sequestration using artificial trees (for more information on geoengineering see the July 2016 edition of the Bulletin, which reports on the Distinguished Guest Lecture on this topic held in March 2016). The benefit of these technologies, Dr Hewett argued, was that they (unlike other proposed geoengineering methods) could be turned off at any time, were we to realise that their negative effects outweigh their positive ones.

Professor Myles Allen took a rather unusual stance on energy, arguing that the public should not foot the bill or make the effort to save energy. Instead, we should create pressure and convince government to make energy companies responsible for mitigating the CO2 they put out into the environment – not by paying a carbon tax, but by mitigating all of it. This mitigation could be done by planting artificial or real trees, or through under-ground carbon storage in natural rock cavities. On the other hand, Professor Allen argued against the introduction of geoengineering via albedo changes: “It’ll never catch on”, he declared, outlining the problems associated with switching it off again, as well as conflicts over governance and the varying effects that it would produce across the world.

Dr Springman’s arguments for a food-based focus initially also centered on climate change mitigation. The speaker argued for a reduction in methane emissions, which contribute around a quarter of the greenhouse gas effect because methane is a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. He proposed several solutions for this, beginning by cutting red meat consumption by 10% to see a fall in methane emissions by 20 to 30% and a concomitant improvement in public health.

Imagine yourself a hundred years in the future. No further changes have been made to mitigate climate change and we are now in an energy crisis, places like Oxford are flooded continuously, and food scarcity is a global problem. What can we do to address and prioritise these issues? At the start of the event, each speaker gave a 5-10 minute talk or “pitch,” followed by an audience vote using Turning Point handsets – an interactive technology that allows live vote collection and data display in Powerpoint presentations. Following the revelation of the votes, the speakers responded, and the story of the future’s crisis unfolded.

Speaking at the event were Dr Caspar Hewett (Newcastle University), Professor Myles Allen (University of Oxford Environmental Change Institute), and Dr Marcus Springman (Oxford Martin School). The event was chaired by Dr Michaela Livingstone from Oxford Sparks, a public engagement platform for science at the University of Oxford.

Dr Caspar Hewett first put forward the case for both large- and small-scale flood interventions, from draining reservoirs before predicted heavy rainfall and digging holes to divert excess water and delay its entry into rivers, to planetary-scale geoengineering approaches. The two geoengineering methods that he supported were the use of “Salter’s ships” spraying seawater into the air to increase Earth’s albedo, thereby reflecting the sun’s rays back into space and cooling the planet, and CO2 sequestration using artificial trees (for more information on geoengineering see the July 2016 edition of the Bulletin, which reports on the Distinguished Guest Lecture on this topic held in March 2016). The benefit of these technologies, Dr Hewett argued, was that they (unlike other proposed geoengineering methods) could be turned off at any time, were we to realise that their negative effects outweigh their positive ones.

Professor Myles Allen took a rather unusual stance on energy, arguing that the public should not foot the bill or make the effort to save energy. Instead, we should create pressure and convince government to make energy companies responsible for mitigating the CO2 they put out into the environment – not by paying a carbon tax, but by mitigating all of it. This mitigation could be done by planting artificial or real trees, or through under-ground carbon storage in natural rock cavities. On the other hand, Professor Allen argued against the introduction of geoengineering via albedo changes: “It’ll never catch on”, he declared, outlining the problems associated with switching it off again, as well as conflicts over governance and the varying effects that it would produce across the world.

Dr Springman’s arguments for a food-based focus initially also centered on climate change mitigation. The speaker argued for a reduction in methane emissions, which contribute around a quarter of the greenhouse gas effect because methane is a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. He proposed several solutions for this, beginning by cutting red meat consumption by 10% to see a fall in methane emissions by 20 to 30% and a concomitant improvement in public health.

|

In the initial audience vote that followed these pitches, the proposed energy measures obtained the most votes, with food interventions a close second and flooding interventions trailing behind (Figure 1). Professor Allen declared the energy problem virtually fixed, with no more net CO2 emissions and with clean-up underway via the already proposed artificial trees. Dr Hewett bemoaned the widespread disasters that would result from neglecting flooding, causing him to propose his same measures again.

Following the first vote, Dr Springman focussed more on the human health element of meat consumption and argued for taxing foodstuffs according to their health impacts and methane content. Such a tax would heavily incentivise micronutrient-rich diets, with significantly lower meat and dairy consumption, escalating the price of a burger to around £30. This suggestion, however, was not popular. The second round of voting saw a swing in the opposite direction, with overwhelming support for flooding interventions. However, the vote rapidly yo-yoed again after governance issues in geoengineering were explored in more depth, “Meat free Mondays” were introduced and Dr Springman went on to propose improving sustainable eating education to caterers, especially in schools, including choosing food with health benefits and lower carbon footprints. The audience were quite taken with this softer approach in the third round of voting; however, Dr Springman argued during questions that education actually has a negligible impact given the resources that go into it, and that taxation, however much we may like burgers and dislike taxing their consumption, is actually much more effective. Professor Allen ended by proposing a rescue mission for Greenland. He argued that, given delays in geoengineering and carbon cleanup according to the vote, the ice may now be melting at a critical rate, risking sea level rises of up to 20 meters, causing huge losses of land worldwide well beyond the localised flooding we heard about earlier, changing sea temperatures and devastating ecosystems. Ending on “a silly note”, Dr Hewett proposed meeting flooding issues halfway, abandoning cities that had been affected and developing new island colonies that employed Venetian-style ocean transport. The final vote saw 46% for “water world adaptions” and 32% to save Greenland (Figure 1). |

Whilst the voting patterns appear indecisive, they might also indicate that all issues were similarly important. But this was not the last vote: no event would be complete without evaluation data, and the handsets came in handy for collecting information. 44% of the audience voted the event excellent, and 25% admitted they had never been to a science event before. Attendees were mostly local, with 87% coming from Oxford/Oxfordshire, 10% from further afield, and 3% from abroad, most having connected to the event through Oxford University or Science Oxford.

Science Oxford runs a year round programme of events for adults and families, which can be explored at scienceoxford.com/events.

Science Oxford runs a year round programme of events for adults and families, which can be explored at scienceoxford.com/events.