From environment to outreach

Researchers are best placed to explain scientific issues to interested members of the public. In recent years, I have been involved in several activities that brought environmental science to a wider audience.

In May 2014, I was part of a team organising Cambridge’s Pint of Science on Earth and Environment, sponsored by the RSC and University of Cambridge. Our speakers included Professor Eric Wolff (a former ECG Distinguished Guest Lecturer) from the British Antarctic Survey, whose research into isotopic abundances and impurity phases in ice cores allows him to dig deep into earth and climate history. The lectures were part of a three-day science gatecrash of pubs in cities around the world that was started in 2012 and runs annually (see pintofscience.co.uk/about). Participating pubs convert back rooms into informal lecture theatres for just three nights, where researchers come to give public talks on what they do. In 2015, Pint of Science expanded, and for the first time took place in Birmingham, where I was then living. Pubs across the city centre—including the cosy upstairs gin bar of the quirky Jekyll and Hyde, where Café Scientifique is held—came alive with inspirational ideas, discussion and narratives of scientific venture.

The distribution, intensity and ongoing demand for Pint of Science show how willing the public are to engage in science, especially with a beer in hand. The next Pint of Science Festival will take place from 23 to 25 May 2016. Look out for events near you.

Early career researchers can also share their research through a range of channels. One such channel is the Brilliant Club (www.thebrilliantclub.org), an award-winning organisation that pairs PhD students and postdoctoral researchers with small groups of school children aged 10 to 18 from state schools from which few students enter highly selective universities. The goal is to increase the numbers of children going to highly selective universities from these schools. The researchers teach a short, intense course on their own research topic and set a final assignment highly challenging for the children’s age group. In 2015, I taught “Environmental Science: Controversy and Chaos” to 24 Birmingham pupils in years 9 and 10, blasting through environmental issues that included the nuclear industry, biofuels, carbon dioxide storage, human impacts on climate, measuring the past climate, and plastic waste. We also talked about social issues surrounding the environment, such as human and economic bias, uncertainty and extrapolation, the value of consolidating evidence, the role of the media, science in advertising, and what “natural” really means. Debate-focussed, the course transitioned from teacher-led to student-led; by the end, I simply gave them some text or a video and watched what they did with it. In their final assignment, the pupils achieved a range of grades from 3rd class to some impressive 1st classes. Early career researchers interested in taking part in this program can get in touch via email ([email protected]).

In May 2014, I was part of a team organising Cambridge’s Pint of Science on Earth and Environment, sponsored by the RSC and University of Cambridge. Our speakers included Professor Eric Wolff (a former ECG Distinguished Guest Lecturer) from the British Antarctic Survey, whose research into isotopic abundances and impurity phases in ice cores allows him to dig deep into earth and climate history. The lectures were part of a three-day science gatecrash of pubs in cities around the world that was started in 2012 and runs annually (see pintofscience.co.uk/about). Participating pubs convert back rooms into informal lecture theatres for just three nights, where researchers come to give public talks on what they do. In 2015, Pint of Science expanded, and for the first time took place in Birmingham, where I was then living. Pubs across the city centre—including the cosy upstairs gin bar of the quirky Jekyll and Hyde, where Café Scientifique is held—came alive with inspirational ideas, discussion and narratives of scientific venture.

The distribution, intensity and ongoing demand for Pint of Science show how willing the public are to engage in science, especially with a beer in hand. The next Pint of Science Festival will take place from 23 to 25 May 2016. Look out for events near you.

Early career researchers can also share their research through a range of channels. One such channel is the Brilliant Club (www.thebrilliantclub.org), an award-winning organisation that pairs PhD students and postdoctoral researchers with small groups of school children aged 10 to 18 from state schools from which few students enter highly selective universities. The goal is to increase the numbers of children going to highly selective universities from these schools. The researchers teach a short, intense course on their own research topic and set a final assignment highly challenging for the children’s age group. In 2015, I taught “Environmental Science: Controversy and Chaos” to 24 Birmingham pupils in years 9 and 10, blasting through environmental issues that included the nuclear industry, biofuels, carbon dioxide storage, human impacts on climate, measuring the past climate, and plastic waste. We also talked about social issues surrounding the environment, such as human and economic bias, uncertainty and extrapolation, the value of consolidating evidence, the role of the media, science in advertising, and what “natural” really means. Debate-focussed, the course transitioned from teacher-led to student-led; by the end, I simply gave them some text or a video and watched what they did with it. In their final assignment, the pupils achieved a range of grades from 3rd class to some impressive 1st classes. Early career researchers interested in taking part in this program can get in touch via email ([email protected]).

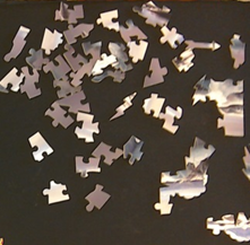

More recently, I have been experimenting with my brand new Science Jigsaws. Pictures kindly provided by friends and researchers are laid onto wooden bases and cut by family-run Puzzleplex (puzzleplex.co.uk/), who create unusual shapes rather than the usual squares to make jigsaw building more challenging and thoughtful. Amongst my small custom collection are such pieces as “The Sun” and “Climate Change”. A picture taken by my uncle and keen nature photographer, Kevin Meehan, “Climate Change” shows a range of spiky icebergs along the coast of Iceland. I’ve tried the jigsaws on adults and children, for example at postgraduate training days and after-school clubs, inviting questions such as “How fast is the ice melting?” or asking them what they know already. As land ice melts, land height rises at 1.4 inches per year according to global positioning system measurements. But what does this mean to young people, and how do they understand the changing climate through stories, images, and science? Motor learning—doing a jigsaw whilst gathering information—is a good way to integrate ideas and creates long-term sensory memories; jigsaw learning can be adapted to any audience.