Evaluation training – Dr Jamie Gallagher

Dr Jamie Gallagher is an award-winning engagement professional specialising in impact narratives and evaluation. Alongside his successful Periodic Table Show, he partners with other institutions to train practitioners in public engagement with research skills. This review focusses on his Evaluation training for public engagement activities, which is delivered online and in person.

Dr Gallagher began the workshop with a clear outline of some key terms and concepts within which he was operating, so as to best identify the aims and metrics for success for the workshop – or, in other words, teaching by example.

Through mastery of technology (including “hold music” and “holding slide”) and opening the online space early, Dr Gallagher created a professional feel for the training. In addition, two inbuilt tea and coffee breaks kept participants refreshed and active, and overall contributed to a positive training experience across his three hour workshop. Throughout, he continued to use a range of online tools, including breakout rooms, messages, and question-taking.

Alas, he found reading and speaking simultaneously somewhat challenging, leading to lengthy silences during which the presenter’s eyes scanned from left to right as he rapidly assimilated the chat content and sporadically brought up relevant points or queries.

Dr Gallagher began the workshop with a clear outline of some key terms and concepts within which he was operating, so as to best identify the aims and metrics for success for the workshop – or, in other words, teaching by example.

Through mastery of technology (including “hold music” and “holding slide”) and opening the online space early, Dr Gallagher created a professional feel for the training. In addition, two inbuilt tea and coffee breaks kept participants refreshed and active, and overall contributed to a positive training experience across his three hour workshop. Throughout, he continued to use a range of online tools, including breakout rooms, messages, and question-taking.

Alas, he found reading and speaking simultaneously somewhat challenging, leading to lengthy silences during which the presenter’s eyes scanned from left to right as he rapidly assimilated the chat content and sporadically brought up relevant points or queries.

The training involved plenty of interactivity. Academics often feel that this is a less efficient use of workshop time, but the truth could not be more different: if they are left to read or think later, few participants will; meanwhile, audience-generated responses, even where compounded or corrected by the training provider, are more readily encoded into our memories. Moreover, by encouraging critical thinking he established an understanding of content that is rarely accessed in lecture format. However, there was also more than ample oration: Dr Gallagher used narrative – proven to activate the brains of the audience and immerse them in the material – and lecture, which is substantially less effective. As such, his Lord of the Rings analogy for choosing the right “ring carrier” remains most fresh in my mind – but I may be a biased audience, as I had heard it before. His training made effective use of case studies and group work, supported by platforms such as his own website and Google Sheets (the latter trialled for the first time during this session), which were seamless in application.

Evaluation tools were approached with a critical eye, and the training not only identified methods for gathering evaluative data (albeit a limited subset of the wide range of available tools), but also invited us to analyse choices and identify potential bias, such as voting stations that use plastic counters and are subject to bandwagonning (swaying voters towards the trend), or offering practical solutions to problems such as flatlining (the phenomenon where form-fillers tick down a vertical line without reading the questions alongside). As anyone who has worked with teenagers will be aware, use of technology to identify smiling and frowning faces is a poor measure of impact: Dr Gallagher pointed out that happy people can frown and unhappy people can smile, and so this constitutes poor evidence for enjoyment. In fact, as he might have added, when concentrating and taking in information, most people wear a blank expression. Dr Gallagher showcased both qualitative and quantitative tools, and did not confine his recommendations to ‘hard science’ metrics, including methods such as thematic analyses which are traditionally employed by the social sciences and executed upon social media or other unregulated sources. Where testimony is concerned, expert testimony may be more meaningful than individual testimony, but individual testimony can provide colour to evaluation when supplied alongside quantitative analyses.

Dr Gallagher drew extensively on the RSC’s Public attitudes to chemistry research report, and reported on its finding as they pertained to evaluation. This research, carried out in 2015, constitutes a comprehensive examination of what the public understand by the term “chemist” and the role of chemists in society. Notably amongst their findings was the ingrained identification of a chemist as a pharmacist – suggesting that past evaluation data that assumed understanding of this difference may be invalid. Findings concluded that avoiding the term chemist and instead discussing scientists who worked on chemistry was far more effective for eliciting helpful responses than attempting to change public perceptions. Also pivotal in the report’s findings was that whilst chemists expected public perceptions of them to be negative, they were actually neutral. These unexpected outcomes have since formed core learning material in the field of evaluation, especially for chemistry.

“Most evaluation is totally awful and completely pointless”, Dr Gallagher declared. Many evaluators begin without clarity of purpose, their evaluation may not be proportionate to their engagement, and they may not consider how questions may be misinterpreted or what they, the evaluators, will do with answers. Every question should serve a purpose. Indeed, in the charity sector, the term “theory of change” is used to describe the backward logic model by which you begin with your final outcomes and work backwards to identify the steps needed to achieve those; evaluation should be no different. That is, questions should be asked to obtain the information needed, rather than chosen randomly and their insights later extracted. If your purpose is to improve your work or your outreach, sidestepping evaluation practices and simply asking your audience may be a better solution. If you are running a one-off project, the number of respondents and integrity of data may not be sufficient to be worth your time – and reflection after the event is one potential alternative.

Evaluation tools were approached with a critical eye, and the training not only identified methods for gathering evaluative data (albeit a limited subset of the wide range of available tools), but also invited us to analyse choices and identify potential bias, such as voting stations that use plastic counters and are subject to bandwagonning (swaying voters towards the trend), or offering practical solutions to problems such as flatlining (the phenomenon where form-fillers tick down a vertical line without reading the questions alongside). As anyone who has worked with teenagers will be aware, use of technology to identify smiling and frowning faces is a poor measure of impact: Dr Gallagher pointed out that happy people can frown and unhappy people can smile, and so this constitutes poor evidence for enjoyment. In fact, as he might have added, when concentrating and taking in information, most people wear a blank expression. Dr Gallagher showcased both qualitative and quantitative tools, and did not confine his recommendations to ‘hard science’ metrics, including methods such as thematic analyses which are traditionally employed by the social sciences and executed upon social media or other unregulated sources. Where testimony is concerned, expert testimony may be more meaningful than individual testimony, but individual testimony can provide colour to evaluation when supplied alongside quantitative analyses.

Dr Gallagher drew extensively on the RSC’s Public attitudes to chemistry research report, and reported on its finding as they pertained to evaluation. This research, carried out in 2015, constitutes a comprehensive examination of what the public understand by the term “chemist” and the role of chemists in society. Notably amongst their findings was the ingrained identification of a chemist as a pharmacist – suggesting that past evaluation data that assumed understanding of this difference may be invalid. Findings concluded that avoiding the term chemist and instead discussing scientists who worked on chemistry was far more effective for eliciting helpful responses than attempting to change public perceptions. Also pivotal in the report’s findings was that whilst chemists expected public perceptions of them to be negative, they were actually neutral. These unexpected outcomes have since formed core learning material in the field of evaluation, especially for chemistry.

“Most evaluation is totally awful and completely pointless”, Dr Gallagher declared. Many evaluators begin without clarity of purpose, their evaluation may not be proportionate to their engagement, and they may not consider how questions may be misinterpreted or what they, the evaluators, will do with answers. Every question should serve a purpose. Indeed, in the charity sector, the term “theory of change” is used to describe the backward logic model by which you begin with your final outcomes and work backwards to identify the steps needed to achieve those; evaluation should be no different. That is, questions should be asked to obtain the information needed, rather than chosen randomly and their insights later extracted. If your purpose is to improve your work or your outreach, sidestepping evaluation practices and simply asking your audience may be a better solution. If you are running a one-off project, the number of respondents and integrity of data may not be sufficient to be worth your time – and reflection after the event is one potential alternative.

Demographics and diversity were discussed, from the prevalence of old white men in science to gathering demographic information on children: the demographics of your chosen speakers, organisers and event managers could inform the visibility of diversity in science, whilst the gender of children attending can be difficult to capture and may not be essential information.

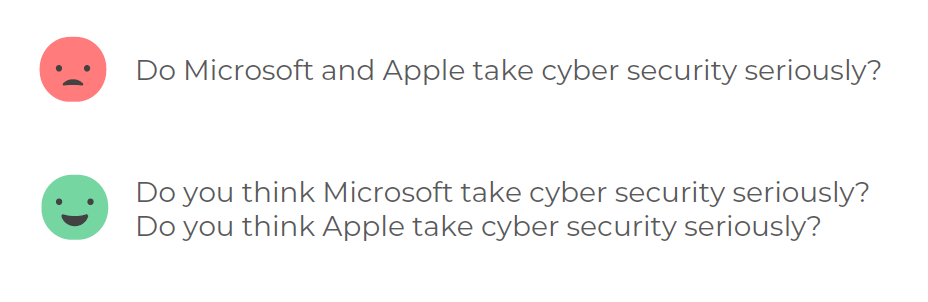

Towards the end of the training, timing must have gone awry; slides were rushed, so we only briefly discussed critiquing evaluation form questions and avoiding fundamental errors such as the use of “and” – which can transform a simple yes/no question into a complex one, where the respondent partially agrees and partially disagrees, especially in the absence of the “don’t know” option.

Overall, Dr Gallagher’s training provided valuable tools for in depth evaluation analysis and critique, prioritising thinking skills that allow the individual to consider their choices over breadth in the field and core information that constitutes the bread and butter of evaluative best practice. His workshops might make a poor introduction to the field, but excellently upskills practitioners who wish to take ownership of best practice science communication.

Resources

You can find out more about Dr Gallagher and the training he offers at www.jamiebgall.co.uk, and read the Public attitudes to chemistry research report at https://www.rsc.org/globalassets/04-campaigning-outreach/campaigning/public-attitudes-to-chemistry/public-attitudes-to-chemistry-research-report.pdf

Towards the end of the training, timing must have gone awry; slides were rushed, so we only briefly discussed critiquing evaluation form questions and avoiding fundamental errors such as the use of “and” – which can transform a simple yes/no question into a complex one, where the respondent partially agrees and partially disagrees, especially in the absence of the “don’t know” option.

Overall, Dr Gallagher’s training provided valuable tools for in depth evaluation analysis and critique, prioritising thinking skills that allow the individual to consider their choices over breadth in the field and core information that constitutes the bread and butter of evaluative best practice. His workshops might make a poor introduction to the field, but excellently upskills practitioners who wish to take ownership of best practice science communication.

Resources

You can find out more about Dr Gallagher and the training he offers at www.jamiebgall.co.uk, and read the Public attitudes to chemistry research report at https://www.rsc.org/globalassets/04-campaigning-outreach/campaigning/public-attitudes-to-chemistry/public-attitudes-to-chemistry-research-report.pdf